Can Excavations Uncover the Truth?

In Ireland, archeologists and forensic scientists are searching for the remains of nearly 800 children who died while in the care of nuns.

OCTOBER 21, 2025

On a quiet summer afternoon in early July, a child thumped a football against a low garden wall on Dublin Road Estate in Tuam, a small town in the west of Ireland. Otherwise, the streets were deserted. Behind the semi-detached family homes and carefully tended gardens, a mass grave had been sealed off with 8-feet-high barriers and 24-hour security. Archaeologists and forensic experts from around the world had gathered in Tuam and were preparing to exhume and attempt to identify the remains of nearly 800 children believed to have been buried there.

The grave lies in the grounds of St. Mary’s, a former Mother and Baby Home where unmarried women who became pregnant were hidden from public view, along with their children. The children who died there were buried in secret, without proper burial records, in what was once a septic tank. There were church-run Mother and Baby homes like St. Mary’s across Ireland; the excavation taking place there now is the first ever state-authorized excavation of such an institution. The results have the potential to prompt further investigations across the country, meaning that countless individuals may finally be able to discover what happened to their missing or deceased relatives. At the same time, the government and those involved in the excavation of St. Mary’s are trying to manage expectations. Despite the scientists’ and archaeologists’ expertise, and their use of DNA sampling and other sophisticated methods, the complexities of sorting through and identifying the remains of hundreds of bodies are such that it is impossible to predict how much the excavation will reveal.

✺

St Mary’s was operated by the Bon Secours Sisters, a Catholic religious order of nuns, from 1925 to 1961. During this period, it took in unmarried pregnant women from all over the country who, told by the nuns that they were sinners, were then forced to relinquish their children. The mothers were sometimes sent away to live in Magdalene laundries, where they were often cruelly abused: in these institutions, women and girls who were viewed to have sinned in some way were made to work for little or no pay, washing, ironing and mending locals’ laundry. Some of the women who gave birth at St. Mary’s remained there while their children were placed for adoption, mostly abroad in countries like the United States. Other children died of malnutrition or disease at the home.

It was a local amateur historian, Catherine Corless, who eventually uncovered the truth. In 2012, while researching the history of St. Mary’s, she discovered that there were no burial records for children who had died at the home.

The home was run by the Bon Secours Sisters on behalf of the local council in Galway, which owned the building. (Throughout the 20th century, the Irish state outsourced significant parts of its health care, education and welfare systems to the Catholic Church.) The home closed in 1961, and the building, which had fallen into disrepair, was demolished just over ten years later. The site has remained empty. For decades, there were suspicions that most of the children who had died at the home had been buried secretly at the site. In the early 1970s, after a new council-owned housing estate was built in the area, two young boys discovered skeletal remains while playing near the site, but locals assumed that they had stumbled on a famine-era grave.

It was a local amateur historian, Catherine Corless, who eventually uncovered the truth. In 2012, while researching the history of St. Mary’s, she discovered that there were no burial records for children who had died at the home. Her request for Galway county council’s records on the home, under Ireland’s Freedom of Information Act, was denied. After painstakingly combing through death certificates and local archives, she found death certificates for 796 children who had died at St. Mary’s, but still no corresponding burial records. She also discovered an official council map of the present-day estate that was built near the site, and the estate’s surroundings. The map contained one ominous detail: a plot marked as “burial ground.” “They [the council] obviously didn’t see the importance,” Corless told The Guardian of the record’s release at the time.

After years of research, Corless published her findings in an article entitled “The Home” in a history journal. The records she compiled show the first baby to die at the home was Patrick Derrane, who died of gastroenteritis in 1925, aged five months. The last was Mary Carty, who died aged four and a half months of a fit, in 1960.

From early 2014, local and international media began to interview Corless and pick up on the story. In June of that year, the Irish government ordered an investigation into St. Mary’s. In 2015, it established the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes, to investigate what had happened at similar institutions across the country.

The government commissioned a test excavation of the site of St. Mary’s in 2017, and analysis of some of the remains it uncovered confirmed Corless’s theory that a mass grave existed beneath the site. It revealed that the ages of the deceased who had been exhumed during the test excavation ranged between 35 weeks and three years old. The dead had mostly been buried in the 1950s. It remains unknown why the nuns did not bury the children in a graveyard or in a more dignified manner.

The nearly 3,000-page Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes report, published in 2021, six years after it was commissioned, estimated that 9,000 children and babies died at 18 institutions similar to St. Mary’s across Ireland between 1922 and 1998. The mortality rate for children in these institutions was about 15 percent, far higher than the national rate during the same period.

The Irish government issued an official state apology following the publication of the report. It also released an action plan promising to provide financial compensation to former residents, as well as other people affected by the institutions, and to push ahead with excavations in the hopes of identifying and reburying remains. The burial site at Tuam, which was the subject of significant public interest due to Corless’s discoveries and the 2017 test excavation, would be the first to be properly excavated.

Rodgers only pieced his own story together decades later. His mother, Bridie, was raped at 16 by a boy who worked on the estate where she had a job as a maid. She didn’t realize she was pregnant until seven months later, and then she lost her job. “She was facing destitution ... She was given the address of St. Mary’s,” Rodgers told me.

But the path has been long and fraught. Legislation empowering the state to exhume and identify remains wasn’t passed until 2022, with the introduction of the Institutional Burials Act. The Covid-19 pandemic and the difficulty of finding the right experts to work on the excavation contributed to the delays.

The Bon Secours religious order still exists, even if not at Tuam. It has offered its “profound apologies” in response to the commission, and an acknowledgement that it “failed to respect the inherent dignity” of women and children in St. Mary’s.

On the day excavation was due to begin, in a cafe a short walk from the excavation site, I met John Rodgers. Nursing a coffee, he reflected on his childhood at St. Mary’s, where he was born and spent the first five years of his life. A lock of his hair and a grainy black and white photo are all he has from those days, tokens his mother held on to when they were separated. “She cut off the lock of my hair when she found out the nuns were going to be separating us. The photo she got a couple of years later … one of the nuns must have taken pity on her or something. It arrived to her in the post without any note,” he said.

Today, Tuam is known throughout Ireland for the cruelty that took place at St. Mary’s. But Rodgers’ painful feelings about the town are mixed with more pedestrian associations: now in his 70s, he remembers Tuam as the home of the ’80s rock band The Saw Doctors and an old sugar factory, one of the area’s biggest employers. His most powerful memories, however, are of the loneliness he felt as a child. The friendships he had with other boys in the home never lasted; the boys would “disappear one after the other,” he said. “To where, I wasn’t aware at the time.”

Rodgers only pieced his own story together decades later. His mother, Bridie, was raped at 16 by a boy who worked on the estate where she had a job as a maid. She didn’t realize she was pregnant until seven months later, and then she lost her job.

“She was facing destitution ... She was given the address of St. Mary’s,” Rodgers told me. After giving birth at the home, Bridie was pressured by the nuns there to give her son up for adoption, but she refused.

“She was able to stay with me for a year and, you know, the bonding process took place. But then she was told they’d found a job for her in Galway and they’d look after me until she got on her feet.”

In reality, Bridie was sent to a Magdalene laundry. There, she washed and ironed for 10 hours a day. At six, Rodgers was adopted by an older couple who lived in a town 20 miles from Tuam. He remembers them as “good people” who looked after him well.

His mother eventually managed to find him and came to see him at the home of his foster parents. He was still young, and his memory of that interaction is hazy, but he recalls his foster parents advising her to flee from the Magdalene Laundry to England, and his foster father giving her the boat fare. She took their advice.

The most important outcome of the excavation will be the reburial of all the human remains found, giving the deceased the dignity they have been denied for decades. But before that, ODAIT will try to identify as many of the remains as possible.

In the end, it was Rodgers who tracked her down again, in 1985, in Northampton, England. By then, he was married and had children. He placed an ad in a paper and received a telegram from her in response. It was “the best day of my life,” he said. They each introduced each other to their spouses, and Bridie met her three grandchildren. They continued to phone and write to each other weekly until she died.

Rodgers is aware that he is luckier than many others — lucky to have survived, and to have been reunited with his mother. “People have lost years trying to find out what became of their relatives,” he said.

✺

The excavation at Tuam is expected to take at least two years to complete and has a budget from the government of €9.4 million for the first year’s work. The team, which includes 18 forensic specialists, has set up offices and a laboratory on the 50,000-square-feet site, where they will conduct preliminary analysis on the excavated remains before sending their findings to a bigger lab.

Daniel MacSweeney, a solicitor appointed by the government as director of the Office for the Authorised Intervention in Tuam (ODAIT), said the most important outcome of the excavation will be the reburial of all the human remains found, giving the deceased the dignity they have been denied for decades. But before that, ODAIT will try to identify as many of the remains as possible.

A report published after the preliminary excavation in 2017 notes that the findings at Tuam could be “more limited than expected,” because of how many bodies were buried there, their commingling and the depth at which they are buried. Identification will be “complex,” it warns.

Doing so requires the help of the community. Around 80 people have volunteered to give their DNA, in the belief they have relatives buried at Tuam. To date, samples have been taken from just 14 of those volunteers; in this first stage, the team is prioritizing excavation work and is only collecting DNA from elderly or vulnerable people. Later, a range of relatives will be able to give DNA, including parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, nieces and nephews of children suspected to be buried at the site, from both the maternal and paternal sides. These individuals’ DNA will be stored at least “for the duration of the project,” said MacSweeney.

It’s not clear how much will be found at the site and how much of what is found will be identifiable. Forensic archaeologist Dr. Niamh McCullagh said many of the remains from the test excavation in 2017 were “commingled,” meaning that their bones are “mixed up and have lost their skeletal order or association.” She and her colleagues will use several methods to separate commingled remains into those belonging to different individuals. “We can sort remains by age at death, and we can try to assign biological sex,” McCullagh said. (One of the ways that McCullagh and her colleagues will assign biological sex is through analysis of peptides in tooth enamel — a method developed in the last few years by scientists at Durham University.) DNA sampling will follow.

DNA sampling is generally considered highly reliable. However, when it comes to skeletal remains, the quality of the samples and the results they produce depend on the conditions of the bone from which samples are taken. A report published after the preliminary excavation in 2017 notes that the findings at Tuam could be “more limited than expected,” because of how many bodies were buried there, their commingling and the depth at which they are buried. Identification will be “complex,” it warns.

McCullagh also expects to find personal items buried among the remains. A shoe was found during the test excavations, as well as objects children at St. Mary’s would have used, such as plates and feeding bottles. Such artifacts will help her team to date the human remains that are found alongside them, she said.

Remains from the excavation that cannot be identified will be buried “in a way that will be decided by families and survivors” in consultation with ODAIT, MacSweeney said.

“How they’re buried and where they’re buried will be decided together,” he said. “You cannot underestimate the complexity of this. It really is an unprecedented situation.”

✺

Some in the area are understandably reluctant to speak to the media. Signs outside homes ask for reporters to respect their privacy. Others are more forthcoming. I spoke to one resident, a young man who did not wish to be named, who came by the excavation site to “pay his tributes” before the works began. He wanted justice to be done, he told me, and felt that this was the sentiment among other residents. Some were “tired of delays,” he said, and looked forward to the day the town could move on. “This should have happened ages ago,” he added.

Also visiting the site was Anna Corrigan, whose brothers John and William Dolan are believed to be two of the children buried under the site. They died at the home in 1947 and 1951, respectively.

Standing by the barriers surrounding the perimeter of the site, Corrigan wept as she read aloud a letter to her mother, now dead. “In 2012, I found out that I had two brothers … Ma, why did you never tell me? … Looking back, I know you loved me, but you never said it, and now I know why. … I’m so sorry for what happened to you.”

Corrigan’s hope is that the excavation will help to tell the stories of the children who died at Tuam, “because I think they’ve been crying for a long time to be found,” she said. “We may not get all the answers, we don’t know. But it’s the next stage.”

“If they find that they are there, it’s the answer, and it’s the truth. I can go to my mother’s grave, and I can tool ‘predeceased by her sons John and William.’ That is the closure, that is the answer, and that is the truth we’re looking for,” Corrigan told a small gaggle of reporters at the site.

Two days later, on July 14, in heavy rain, the diggers broke the first ground behind the gates of the excavation site.

The excavation started in two areas: a former workhouse yard and the high stone boundary wall at the eastern side of the site. The plan is to move gradually westwards across the site, a methodical approach designed to minimize the risk of missing or damaging anything that’s buried. In the workhouse yard, excavation was conducted by machine; in the latter, by hand. Since work began, excavators have found five sets of human remains that date from a period before the home’s existence as well as some other human remains that have yet to be analyzed. Many animal remains have also been uncovered, along with personal items from the institutional era: shoes, spectacles, glass baby bottle feeders.

Corrigan’s hope is that the excavation will help to tell the stories of the children who died at Tuam, “because I think they’ve been crying for a long time to be found,” she said. “We may not get all the answers, we don’t know. But it’s the next stage.”

For John Rogers, coming back to Tuam is never easy. “I’ve spent my life leaving. Leaving the family home, leaving so many other places, whether it was cities, towns, workplaces,” he said. “But I’m very proud that I have some of the traits of my mother,” he added, his voice catching. “I’m very resilient, and I’ll keep coming back until there are answers.”

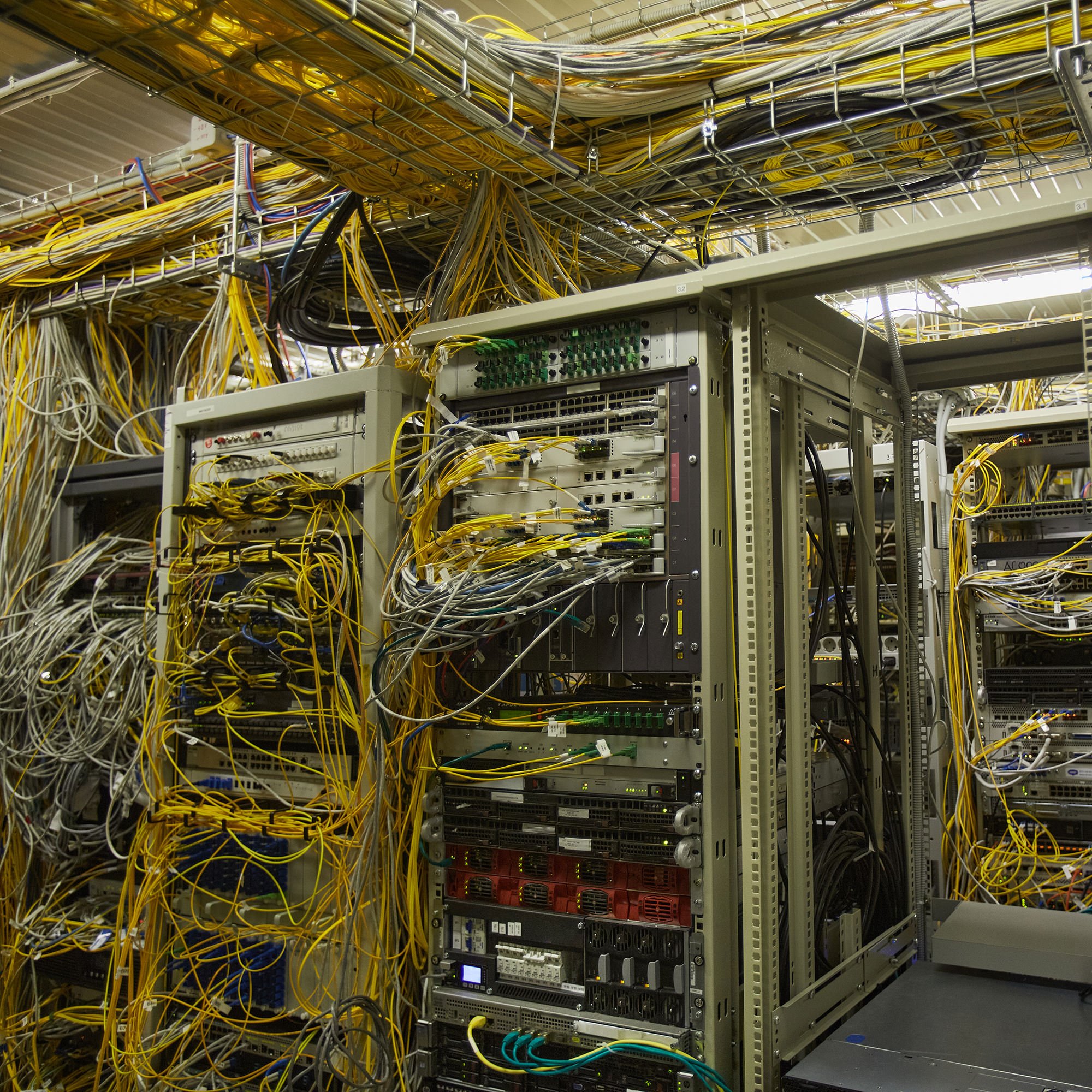

PHOTO: View of the mass grave at the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home Tuam County Galway Republic of Ireland by Auguste Blanqui, 2019 (via Wikimedia)