“Welcome to Hell”

A dispatch from Europe's largest arms fair, where tanks, missiles, and guns are on the market.

OCTOBER 26, 2023

The weapons industry — an estimated $112 billion industry, though that number, given the secretive and unregulated nature of defense, is likely to be much higher — remains an industry with the same outward mechanics as, say, pharmaceuticals or pet food. There is merchandise, there are buyers and sellers, there is inflated market demand, and there are trade shows. On the first day of the biennial Defence & Security Equipment International (DSEI), one of the world’s largest international arms fairs, I caught the Elizabeth Line from Tottenham Station and rode toward London’s ExCeL Center, the city’s biggest convention space. It was eight in the morning on a surprisingly warm September day, and even amongst the morning work rush, the convention attendees stuck out. A group of middle-aged Israeli men came into the carriage rolling small suitcases. They sat down and began taking selfies, laughing and joking with each other. When we arrived at our stop, they pulled out their DSEI badges and headed to the entrance.

The first DSEI was held in 1999, after the British government privatized the joint British Army and Royal Navy Exhibitions. On the morbidly auspicious date of September 11, 2001, DSEI moved to its current location at the ExCeL Center in East London, where it has remained ever since. ExCeL hosts a range of expos; in the weeks following DSEI, it put on a street food business expo and a dentistry show. This year, over 1,500 exhibitors from 74 countries attended, showcasing the latest advancements in military, aerospace, and naval technology. The goods on display range from the mundane — bolts and springs used in repairing various machinery, and battle-field ready food packages — to the bewildering, including gigantic tanks with rocket shooters affixed to their hoods, futuristic guns and submarines, missiles that can leave craters where homes once stood.

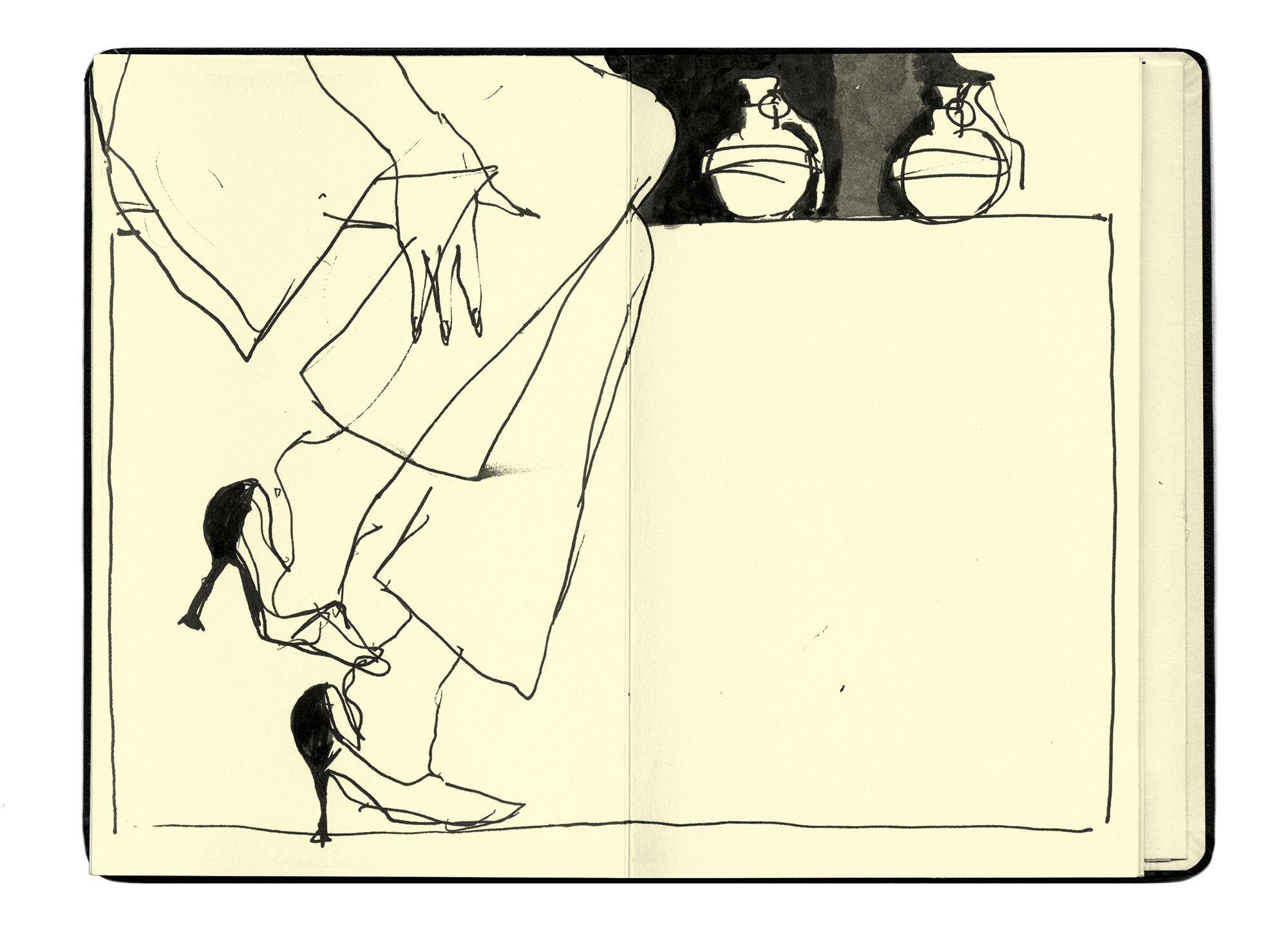

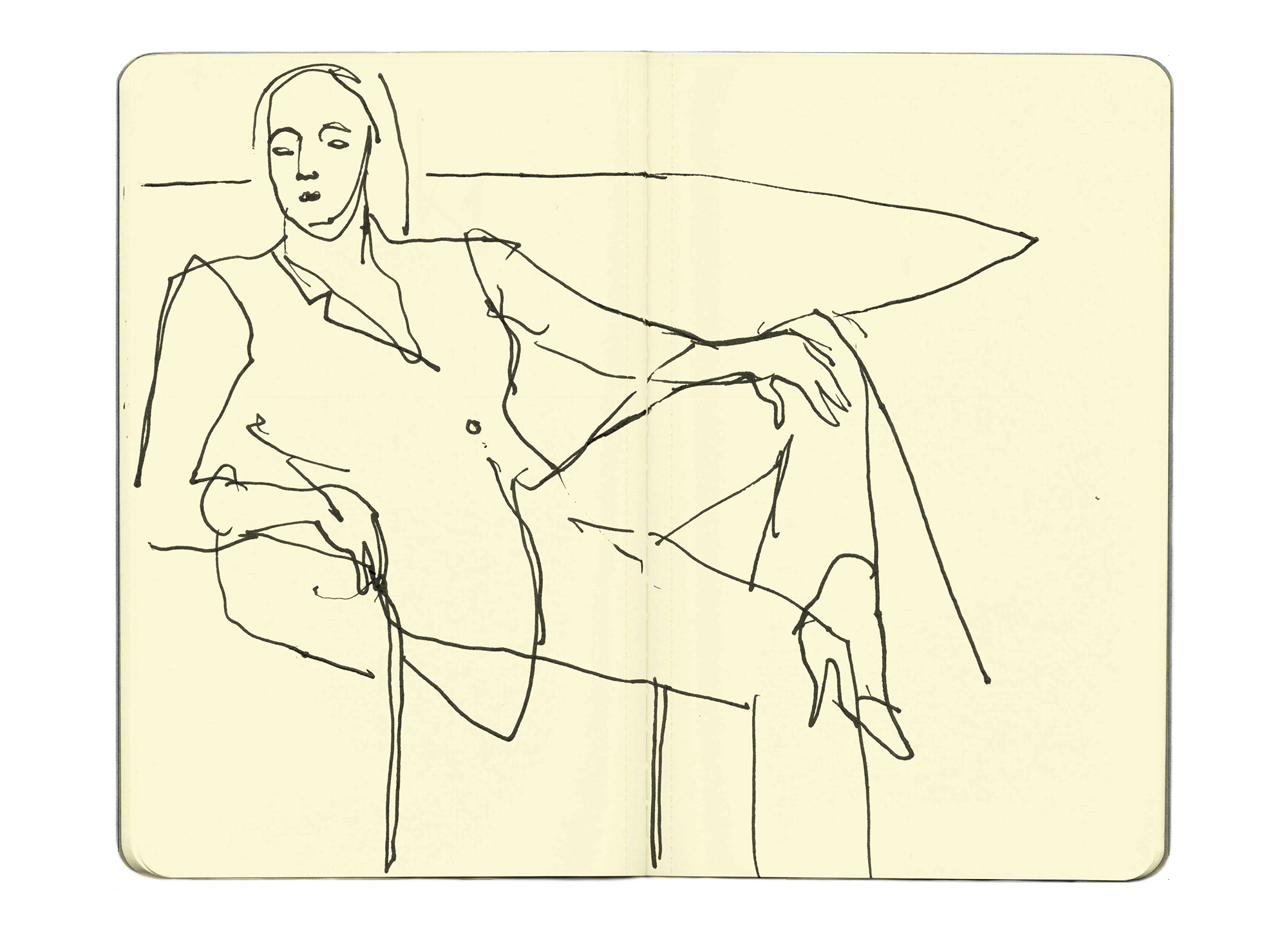

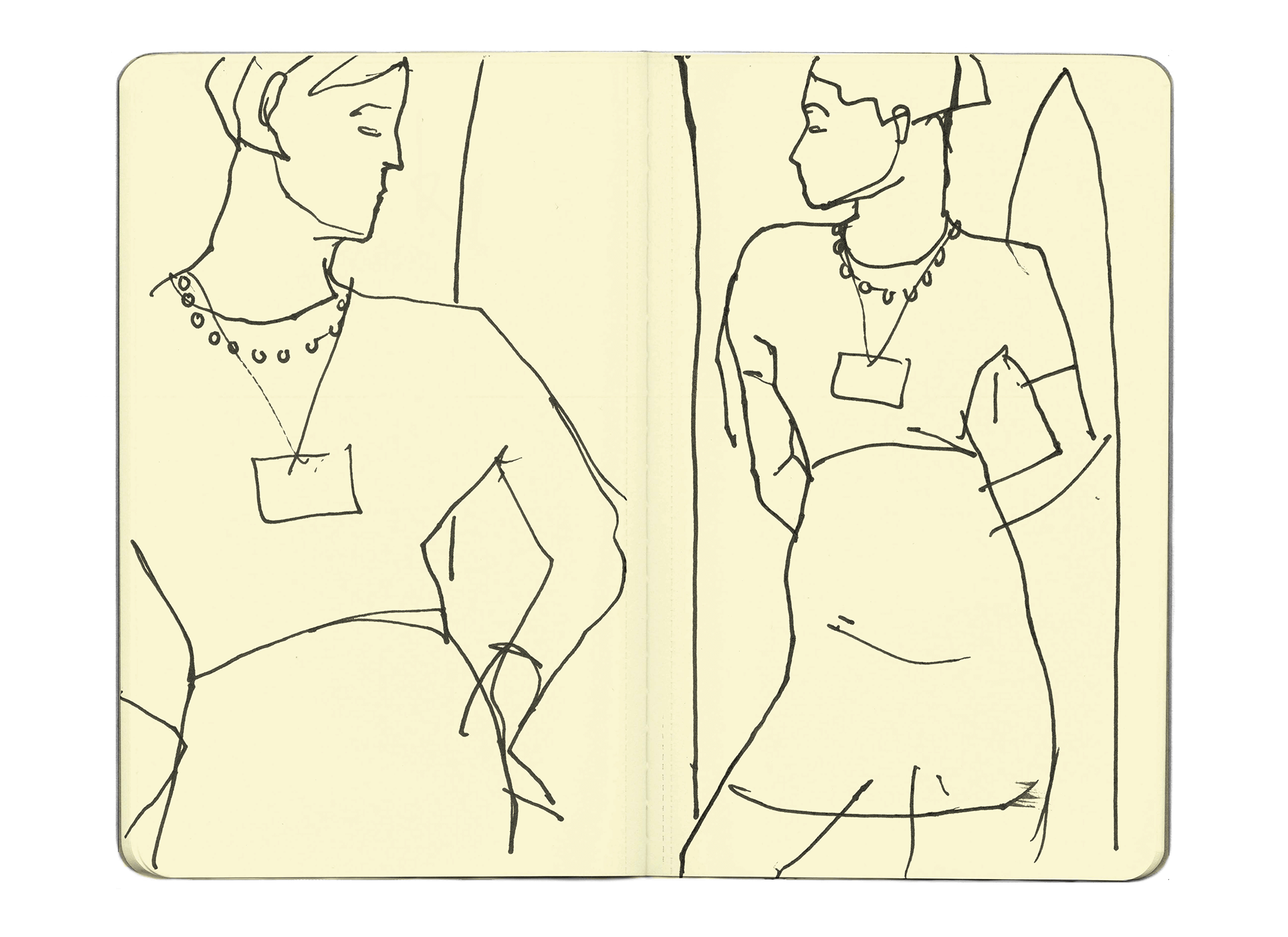

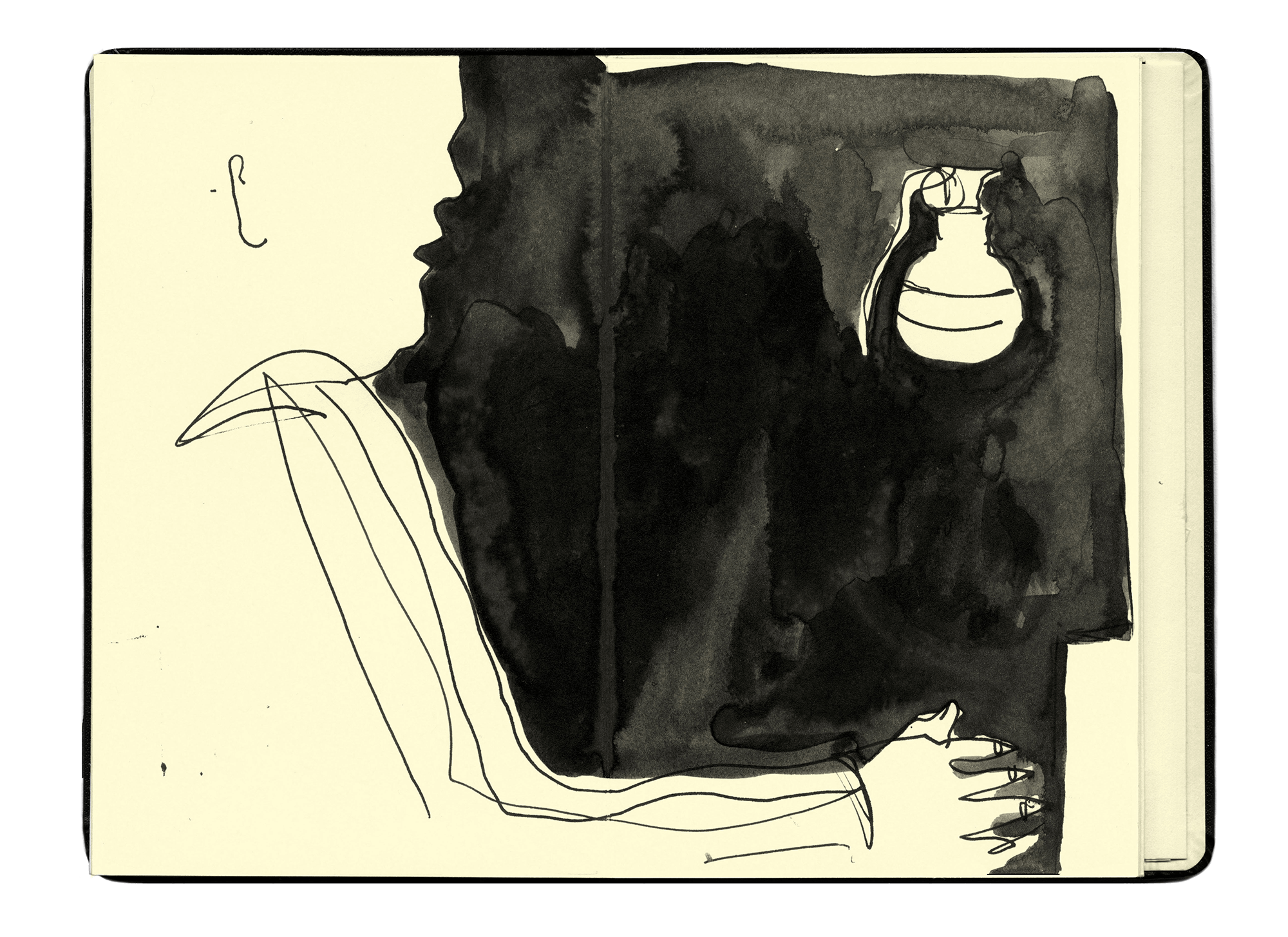

Sketchbook drawings, DSEI 2023 by Jill Gibbon

Placed in the sanitized context of the ExCeL center, with its fluorescent lighting and purple carpeting, one can almost forget that these objects, on display in London, are designed to be used in warfare in far off places. The fair’s pomp further exaggerated this feeling: At the South Korea pavilion, a stand enticed attendees to have their names written in Korean calligraphy on sheets of rice paper. Ateşçi, a small arms producer based in Turkey, had a three-piece band playing classical Turkish music. Vendors handed out stress balls in the shape of hearts, umbrellas, notebooks, pens, and candy (“Welcome to Hell,” the wrappers read at the stand for AB Bofors, a Swedish arms manufacturer now owned by the British company BAE Systems). Several of the pavilions and stands had open bars, and people started drinking early in the day; smoke breaks were taken outside under the shade of BAE Systems’ Eurofighter Typhoon, a 16-meter long, 11-ton supersonic aircraft. It had been elevated and was a popular spot for selfies.

The surreality of DSEI stems from what is left unspoken: these weapons kill people, often indiscriminately, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians. The connection between what these weapons are and what they can do is conveniently scrubbed clean. “When we collaborate, we close the gaps our adversaries are looking to exploit — and build a safe, secure and sustainable future,” one sign read. “Passion for technology,” the Rheinmetall stand announced. “Ensuring those we serve always stay AHEAD of READY,” proclaimed Lockheed Martin. All this serves to reduce the weapons industry to one simple concept: defense. Manufactured explosive weapons, which account for 77 percent of civilian casualties in Ukraine, were also on display, as were drones, which are used by countries including the United States to conduct airstrikes, often in direct violation of international law.

Everyone is here, and everyone is shopping.

DSEI serves the same purpose as any other industry event: to meet, to show off new technology, to deepen pre-existing relationships and strengthen new ones. Companies and countries also announce new sales at the convention — this year, for example, Paramount Aerospace Industries announced its collaboration with the Democratic Republic of the Congo. “The people who run DSEI probably see themselves as good people,” Andrew Feinstein, Executive Director of Shadow World, and the author of Shadow World: Inside the Global Arms Trade, told me. “But these companies and fairs have created such astonishing immiseration around the world that they’ll never acknowledge.”

✺

Large-scale arms trading has been part of statecraft since at least the early 17th century, but the arms trade of today — an artificially inflated industry with an unnaturally close relationship to government marked by extreme corruption — is a more recent phenomenon. The United States remains the largest military spender in the world; last year, its annual defense spending increased by $71 billion, to a total of $877 billion. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), total global military expenditure increased by 3.7% in 2022, reaching a new high of $2240 billion. Between 2013 and 2022, global spending grew by 19% and has risen every year since 2015 — a stark contrast, to say, healthcare expenditure (estimated 6% growth) during the pandemic. In 2020, at the height of Covid-19, the U.K. boosted its defense budget by $21.9 billion, the largest rise in spending since the end of the Cold War.

Today, the United States is the largest supplier of arms worldwide. The symbiotic relationship between governments and arms companies, particularly in the United States, was cemented during George W. Bush’s presidency. He stacked his cabinet with former defense contractors, especially ex-employees of Haliburton and Lockheed Martin; those companies were the two biggest beneficiaries of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. In 2005 alone, Lockheed Martin received $25 billion in taxpayer money — more than the GDP of over 100 countries. Lockheed Martin had a sizable pavilion at DSEI, and on display was a small-scale version of the F-35 jet, the subject of the world’s costliest weapons system, totaling $1.7 trillion of U.S. taxpayer money. It is supposed to replace the F-16, the main fighter jet for three branches of the U.S. military, and it barely works. Its mission capable rate is 55%, well below the Pentagon’s goal of 90%.

Studies have suggested that corruption in the arms trade contributes roughly 40% of all corruption in global transactions. “A number of systemic features of the arms trade encourage corruption, of which two are particularly important. First, its deep and abiding link to matters of national security obscures many deals from oversight and accountability. Second, the rubric of national security facilitates the emergence of a small coterie of brokers, dealers and officials with appropriate security clearances,” a 2011 report from SIPRI found. “These close relationships blur the lines between the state and the industry, fostering an attitude that relegates legal concerns to the background.”

Feinstein, a former politician in South Africa, began investigating the arms trade after he witnessed first-hand the extreme corruption in newly democratic South Africa. In the years leading up to the end of apartheid in 1994, European arms companies began courting South African politicians, leading to a $5 billion arms deal in 1998 to purchase trainer and fighter aircrafts, submarines and helicopters for the country. As much as $300 million was paid in bribes at a time when South Africa faced no external threats, and was dealing with internal crises like unemployment and wide-spread HIV rates. No one has been brought to justice in the South African case, and Feinstein has gone on to record 502 violations of UN arms embargoes around the world; only two have resulted in any action. When companies are orchestrating deals worth billions of dollars, even a fine of several hundred million is a drop in the bucket.

“DSEI is not a separate world, it’s the world we live in made visible.”

One of the best examples of the corrupt, unwieldy nature of the arms trade — and its reliance on bribes, or kickbacks as they are more commonly referred to — can be found in the industry’s most well-known deal, Al-Yamamah, in 1985. British Aerospace (which merged with Marconi Electronic Systems and others to form BAE Systems in 1999, Europe’s largest defense contractor) had been privatized by then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. With the company on the brink of financial ruin, the U.K. orchestrated a £43 billion deal with Saudi Arabia. The Serious Fraud Office, following a series of investigations by the Guardian newspaper uncovering what they initially thought to be a slush fund for the Saudi Arabian royal family, actually realized that the deal included £6 billion worth of bribes (including, allegedly, £8 million in kickbacks for Thatcher’s son, Mark, leading to the British press nicknaming it the “Who’s Ya Mama?” deal). After five years of digging, the SFO was ready to bring charges against BAE Systems. Instead, Tony Blair personally stepped in to halt the investigation — first on a claim of insufficient evidence, which was refuted by the SFO, and later on national security grounds. Blair claimed the Saudis had threatened “blood on the streets of London” if the investigation persisted. The SFO abandoned the investigation and no charges were filed. Even left unsaid, the response was clear: money reigns supreme.

This being London, BAE Systems was the crown jewel at DSEI. It had one of the biggest, brightest, shiniest pavilions: two levels featured suspended weapons, backlit ammunition, a refreshments area, and a small stage for talks. A sound system churned out a looping thump of soaring video-game music that immediately spiked my heart rate. Someone had left two milky cups of tea on the display for the Archerfish Mine Disposal System. I slowly worked my way around the pavilion, walking up the raised platform which affords attendees a 360 view of the submarines, tanks, jets, and missiles on display. I stopped in front of the display case for the Next Generation Adaptable Ammunition. A young blonde man, baby fat still visible on his cheeks, was standing in front of the case wearing a BAE Systems lanyard. He was the lead engineer on the project, and he wants to tell me all about it — he explains that he and his team had managed to double the missile’s range capability, meaning it can now travel up to sixty kilometers before exploding. The missile will be available for sale in 2025. Despite my prominent badge, he did not immediately realize that I was a journalist.

“How do you feel knowing this missile you made will likely be used to kill civilians?” I ask. “How do you feel working for a company that has sold arms to Saudi Arabia, which have then been used to kill over 15,000 Yemeni civilians since 2020?” He told me these were good questions, deflected, and moved on.

An animatronic mannequin dressed in a camo poncho has been programmed to shoulder shimmy on loop, like some sort of haunted soldier.

The veneer of corporate respectability only works if no one prods it. “Most people think, quite understandably, that weapons are produced for defense,” Dr. Jill Gibbons, a professor at the Leeds Beckett University’s School of Arts and the author of the upcoming book Etiquette of the Arms Trade: Undercover Drawings, told me. For the past ten years, Gibbons has been surreptitiously entering arms fairs under a pseudonym and a sham company, collecting company gifts and drawing what she refers to as the ‘gestures’ of weapons networking. “But they are not,” she continues. “It’s just about selling weapons. It’s just making that visible. The whole thing is built on an absolutely insupportable pretense.”

In past years, DSEI exhibitors have hawked weapons that are banned under international law, including cluster bombs. This year, ten of the 74 invited countries, including Pakistan, Iraq, and Israel, are on the U.K.’s list of Human Rights Priority Countries, a designation that signals particular “concern about human rights issues, according to the government’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office. Much of the chatter around DSEI — indeed, the weapons industry in general — has been around bolstering defense for Ukraine. To that end, Russia is not officially invited (Russian exhibitors have not attended since the invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014). Turkey and Saudi Arabia are both in attendance, with dozens of vendors and enormous pavilions. Israel has one of the largest pavilions at DSEI; its occupation of the Palestinian territories is illegal under international law, and its bombing of Gaza constitutes war crimes, according to Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. Then there is of course the presence of countries like the United States, which itself illegally invaded Iraq under the UN Charter. Everyone is here, and everyone is shopping.

“DSEI is not a separate world, it’s the world we live in made visible,” says Gibbons.

I picked up a notebook from Babcock International, a British defense company, made from recycled wood. It's engraved with the phrase “Creating a safe and secure world, together.” In January 2023, the U.K. Navy ordered an investigation into the defense company after it had been hired to fix one of their submarine’s nuclear reactors. They uncovered that Babcock engineers had used superglue to fix the reactor’s broken bolts, which should have been replaced. A group of U.K. industry suppliers walk past the BCB International booth. An animatronic mannequin dressed in a camo poncho has been programmed to shoulder shimmy on loop, like some sort of haunted soldier. “Well that’s scary,” one of the suppliers says, before turning to the BAE Systems pavilion. He makes a beeline for the SSN-AUKUS Submarine Model, a nuclear-powered, conventionally-armed submarine that can be used in underwater warfare.

✺

There were protests, too. On the opening day of DSEI, I spoke with the demonstrators gathered outside the convention center. There were about thirty, some dressed in eye-catching outfits like glittery leggings and bright orange vests, others holding up bloodied prosthetic limbs. I spoke with Jinn, a young woman who runs Demilitarize Education, an organization that aims to break U.K. university ties with the arms industry. “Our presence is needed and important,” she told me. “The momentum is building. They can’t get away with selling weapons of arms from our capital city forever.”

Men stood with their hands on their hips in front of missiles that were level to their groins; the symbolism was tiring.

I asked her if she has any hope that things could change. “The common reaction from these people is to say if we didn’t do it, someone else would. That’s absolute bullshit,” she said. “I do have hope that things will change. That's why I do the work I do.” I head back inside the fair with some other attendees, where protestors have partially blocked the first entrance. “Murderer!” one woman wearing a bodysuit covered in stuffed animals screamed at us. I stopped in front of a group of middle-aged British military men, in brown service dress.

“You can try to block me, but I’m coming in whether you like it or not!” one of them told his friend. He laughed heartily and takes a huge puff of his e-cigarette. The smoke enveloped his head and when it dissipates, the smile hangs limply on his face.

The majority of the people at DSEI were men, and the energy pulsing through the ExCel center was undoubtedly masculine. Men stood with their hands on their hips in front of missiles that were level to their groins; the symbolism was tiring. The arms industry, though, has excellent P.R. and knows the importance of an up-to-date image, As such, there has been a concerted effort to bring more women into the fold. At the Ultimate Training Munitions shooting booth, I watched as a woman dressed in a blue shift dress and pearls, gleefully shot a rifle; there was an entire panel dedicated to diversity in defense. “There are a huge number of women in tight dresses and stilettos who just hold that power structure in place,” said Gibbons. She noted that this year was more subdued — in the past, there have been fashion shows with young female models strutting on raised catwalks above missiles — but most of the booths have smiling women manning the front desk; the actual exchange of power happens behind them, largely between men.

The ferocity of Israel’s retaliation has been a boon for the industry, as the war has already caused a global surge in weapons purchases and trades.

On my last day at DSEI, I visited the Elbit Systems pavilion. Elbit is the largest manufacturer of weapons for the Israeli government and one of the largest growing defense contractors in the world; they have six subsidiaries and nine factories in the U.K. Best known for their unmanned armed drones, Elbit has been accused of testing their weapons on civilians in Gaza and the West Bank. Their U.K. factories have been the routine target of civil disobedience by Palestine Action, whose actions resulted in one of the factories being shut down. Elbit Systems has slammed Palestine Action’s activism as “criminal.” Over the past several weeks, Palestine Action has continued to target Elbit Systems, in addition to fifty U.K. companies that it claims support the Israeli arms supply chain. Israel has reportedly dropped more bombs in Gaza in the first six days following Hamas’s Oct 7 surprise attack than the U.S. did in any month during its coalition war against ISIS. The ferocity of Israel’s retaliation has been a boon for the industry, as the war has already caused a global surge in weapons purchases and trades. At time of publication, over 6,500 Palestinians, according to the Gaza Health Ministry, had been killed by the sorts of weapons on display at DSEI; nearly half of the dead are children.

At the Elbit pavilion, I walked up to the blonde woman at the front desk and introduce myself. “Are you writing this from an international perspective?” she asks me in a clipped British accent. I asked her what she could possibly mean — surely everything here is international — and she evaded the question. “I can tell you right now, based on who you write for, you’re not going to be granted an interview,” she told me. Within minutes, several people from Elbit swarmed around me. I proceeded to ask questions anyway: How has the failed arms deal impacted the company? Will more factories close? How do they justify working for a company that routinely kills civilians, including women and children? “No comment,” they all said. After several awkward minutes, I stepped away from the desk and back into the pavilion. A man followed me inside.

“Mark,” I said, squinting at the nametag of a stocky British man, “would you like to answer a few questions for me?”

“You’re going to have to leave the area,” he told me.

✺ Published in “Issue 9: Weapons” of The Dial

JILL GIBBON is a British artist whose work focuses on the international arms trade. Her drawings have been exhibited internationally, and are in the permanent collections of the Imperial War Museum, and Peace Museum. Her new book, Gifts from Arms Fairs, will be published early in 2024, co-authored with photographer Ricky Adam.