Undoing the Alhambra Decree

Is Spain’s citizenship program for Sephardic Jews the best way to right past wrongs?

JUNE 6, 2023

In 1492, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile issued the Alhambra Decree, forcing Spanish Jews to convert to Catholicism or flee Spain.

In June 2015, the Spanish parliament passed a law allowing people with Sephardic ancestry to apply for citizenship, in effect reversing the edict of expulsion. The law claims that, despite five centuries of estrangement, the “children of Sefarad maintained a nostalgic link impervious to changes in language or generations.” (“Sefarad” is the Hebrew word referring to the Iberian Peninsula). The preamble to the law describes Sephardim as a people without “rancor,” who continued to “love” their former home despite Spain’s five-century-long “silence.” The text casts Spain as a nation that has been “mired in forgetfulness,” which hopes to achieve “definitive reconciliation” by way of the new measures.

Citizenship as a form of reparations for 20th-century atrocities is not uncommon in Europe. Descendants of those persecuted by the Nazis, forcibly stripped of their German nationality, can obtain German citizenship; those whose families fled Spain under Franco’s dictatorship are eligible for repatriation. The law for Sephardim, however, is distinct by virtue of its temporal scope, seeking to redress wrongs committed nearly half a millennia ago.

When the law first passed, the press hailed Spain for passing a piece of historic legislation, but it was not the first measure of its kind. Spain had previously offered a specialized naturalization pathway for Ottoman Sephardic Jews through the Royal Decree of 1924. The decree was an attempt to help Spain maintain political and economic sway following the birth of the Turkish Republic by offering naturalization pathways to “protegidos españoles” with “origen español” —coded language referring to Sephardim. (The decree allowed some Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews an escape route during World War II.)

Although the Decree expired in the 1930s, it set a legal precedent for the “special link” between Spain and the Sephardim—the law likens this “special link” to the one between Spain and Latin Americans, to whom Spain also offers accelerated pathways to citizenship. Starting in the early 2000’s, a small group of Sephardic Jews, particularly from Turkey, had identified the privilege given to Sephardim when applying for Spanish citizenship. For Sephardim with purchasing power, Spanish citizenship has been possible since the early 20th century.

When the 2015 law was passed, those who were eligible only had three years to apply, later extended to four. Between 2015 and 2019, each applicant had to obtain a certificate proving their Sephardic origin. Before 2020, applicants could solicit a certificate of Sephardic origin from various official organizations, like synagogues and Jewish communities in their countries of origin or current residences. After 2020, the certificate had to be issued directly from the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain, a group which claims to represent the various Jewish groups in Spain, but excludes La Comunidad Judía Reformista de Madrid, Madrid’s reform synagogue.

The application required proving basic knowledge of the Spanish language, the Constitution, the nation’s history, and its culture in tests administered by the Cervantes Institute, and a “special connection” to Spain beyond their ancestry. A “special connection” to Spain could come in the form of studying Spanish history at an accredited institution, knowledge of Ladino or Hekatia (the extant Judeo-Spanish languages), blood relatives who were naturalized due to the Decree of 1924 or 1948, or “fulfillment of charitable cultural, or economic activities to the benefit of Spanish persons or institutions or in Spanish territory.” In order to formally present this documentation, each applicant also traveled to Spain to sign before a notary.

As soon as a politician from the Partido Popular, a Christian-democratic party with Francoist roots, proposed a law of return for Spanish-Jews in Parliament in 2013, it inspired controversy. Izquierda Plural, the electoral alliance comprising 13 left-wing parties from 2011 to 2015, proposed an amendment to include descendants of Spanish Muslims who were expelled in 1610. This amendment was ultimately rejected by conservative lawmakers. “Why would the descendants of Spanish Muslims not have the same opportunity if the objective is … to reconcile Spain with its past?” wrote the journalist Ignacio Cembrero in a column for El Mundo. This hypocrisy led Cembrero and other commentators to speculate the law for Sephardim was proposed for economic reasons, or as an effort to appease Israel after Spain voted to recognize Palestine in the United Nations, or as a retaliation for the Catalan separatist movement.

The Spanish government received 132,000 applications through this pathway until October 1, 2019. As of July 2021, 34,000 applications had been accepted. The following accounts of the application process testify to the complexity of reparative citizenship more than five hundred years after the rupture between Sephardic Jews and Sefarad.

Selin Sarhon, 27, Madrid

As a girl, Selin Sarhon knew her history. Her mother made sure of it. She knew about her ancestors’ flight from Spain and their eventual refuge in the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Bayezid II, who valued their trading acumen. She knew about the Istanbul neighborhood of Kuledibi, huddled around Galata Tower, which became home for many Sephardic, Ladino-speaking families. She knew that after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, Turkish replaced Ladino as the lingua franca in Sephardic homes. While her mother serves as the editor-in-chief of the only Ladino newspaper, El Amaneser, Sarhon was never taught Ladino.

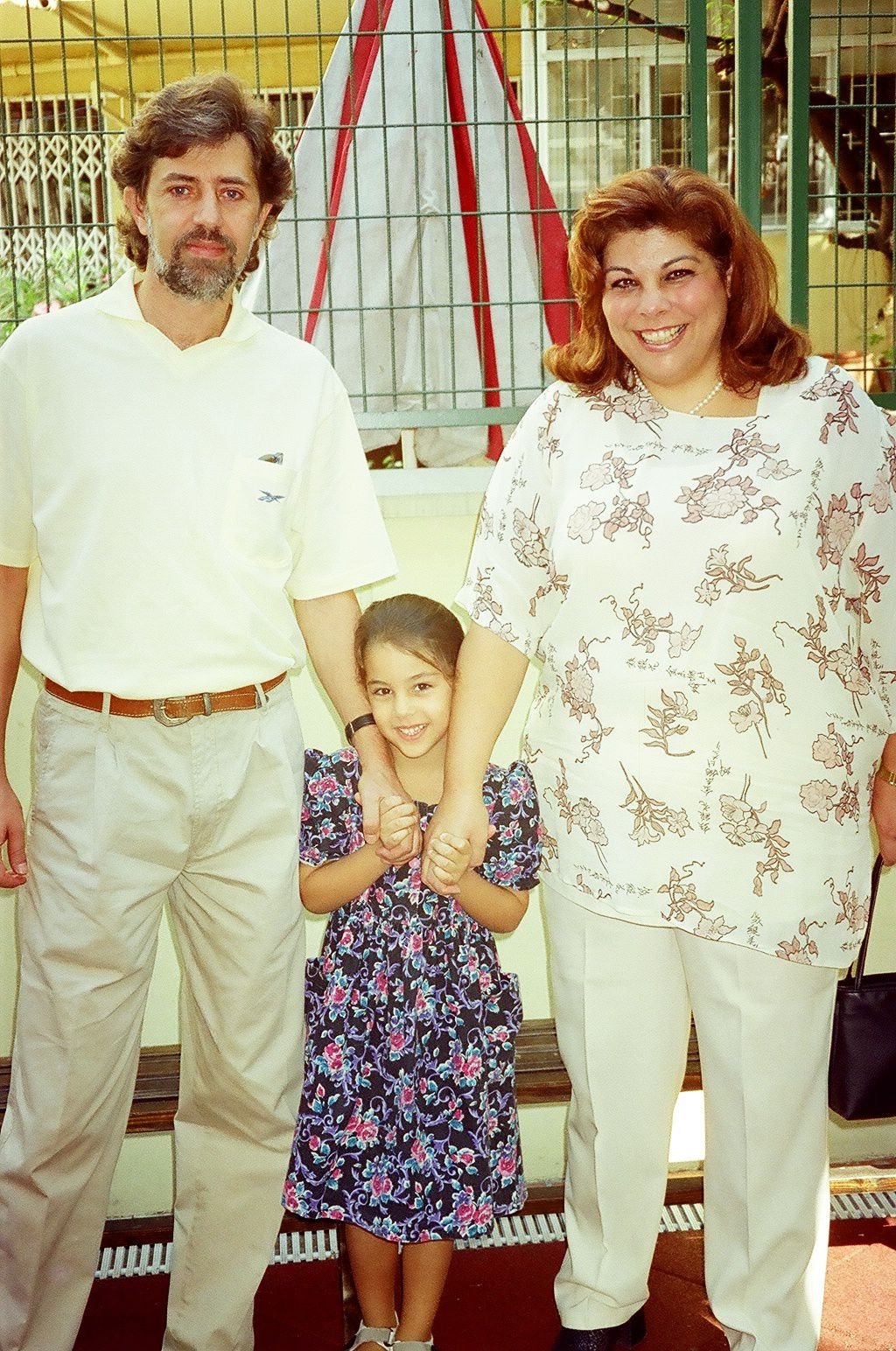

Sarhon had always planned to live outside of Turkey. In 2009, when she was thirteen, her mother and father arranged the necessary documents and applied for Spanish citizenship under the special condition of their Sephardic ancestry. This passport meant Sarhon could live and work throughout Europe and travel with ease to 194 countries, a contrast from her Turkish passport. After attending university in Tel Aviv, Sarhon moved to Madrid, as a Spanish citizen, to teach English.

A young Selin with her mother Karen and father Jozi.

I was born in Istanbul. I grew up there. My parents met in the Sephardic community. When they were growing up, they used to do theater together.

One of their biggest shows was about Sephardic life in Istanbul in the 1930s. The Galata Tower is around the area where all of the Jews lived. The play is called Kula, which in Turkish is ‘kule,’ which means ‘tower.’ The only people that could really understand the full play were Sephardic Jews, because it was staged in a combination of Ladino and Turkish. My dad directed, and my mom acted.

My mom says it was my fault, I never wanted to learn Ladino, but I think it's her fault for not wanting to teach me. I think it was always easier back in the day. It was always from mother to daughter, the language, because they were at home. When the Turkish Republic was started, women started to go back to work, and we started to lose that language at home. At least this is how my mom always tells it to me. Even though I never learned it — now I can of course, now that I speak Spanish — it's in your head, it's in your blood, it's in your ears all the time.

“I know it helped a lot of very rich people get it very fast, which was great for the rich people. But what about the rest?”

I went to a Turkish school, but there were a lot of Jews in my class. So I always felt kind of a mix of both, and not fully part of either. A lot of my friends from Turkey managed to leave.

If history hadn’t happened the way it did, we might have still been in Spain. I understand this [law] is an “apology.” It is good that they’re trying to atone for their mistakes in the past.

The one thing I wish they would have handled differently is [the] deadline. A lot of people either weren't aware or didn't have the means to actually meet the deadline, so it kind of got cut off in the middle. If you're going to apologize and offer this opportunity to people, why have a deadline? Offer this for longer, at least. I know it helped a lot of very rich people get it very fast, which was great for the rich people. But what about the rest?

Sara Stayerman, 32, Stockholm

At a Shabbat service at Templo Hebreo Maguen David, a tallit partially covering her mushroom-top hair, Sara Stayerman rests on her mother’s hip. Before her is a table covered with white cloth and set with Shabbat candles dripping wax. Another woman holds Stayerman’s dimpled hand aloft, as if showing her the typical prayer motion—wave your hands three times to gather the light, raise your light-filled hands to shield your shut-eyes—that accompanies the blessing.

“This is my mom teaching me the shabbat candle blessing while pregnant with my brother,” Stayerman wrote when she sent me the photograph on WhatsApp. It was from the early 1990’s in San Pedro Sula, Honduras.

Before a judge, she had to swear loyalty to the King of Spain. She was assigned to perform this rite before Jose María Celemín Porrero, a judge with a documented history of discrimination toward Latin Americans seeking Spanish nationality.

Maguen David, a white, colonial-style building emblazoned with a gold Star of David, is one of two synagogues in Honduras. It was founded by Stayerman’s paternal great-grandparents who arrived in the country before World War II.

Stayerman submitted her application for Spanish citizenship in December 2017. In 2020, she was notified that her application had been accepted. At the time, she was living in Getafe, a quiet suburb south of Madrid. Her lawyer prepared her for the next step. Before a judge, she had to swear loyalty to the King of Spain. She was assigned to perform this rite before Jose María Celemín Porrero, a judge with a documented history of discrimination toward Latin Americans seeking Spanish nationality.

A decade prior, El País and El Mundo reported on an investigation into Celemín Porrero’s conduct. Latin Americans testified to filing into his office expecting to recite an oath, instead facing a stream of questions to assess their “españolidad,” or “Spanishness.” El Periódico, a daily paper in Barcelona, quoted him asking “What happened in Spain in 1868?” and “What are the absolute values of the Constitution?” He was also known to pose questions regarding Spanish post-war poets and Spanish surrealists, ingredients for a tortilla de patata and names of battles during the Civil War. The General Council of Spanish Lawyers released a statement that his questions “exceeded the level of general knowledge.” Despite all this, the Supreme Court Justice in Madrid found no evidence of discrimination and Celemín Porrero maintained his position.

Stayerman received her Spanish passport in May 2022.

Celebrating Simchat Torah in Honduras, when Sarah was nine years old.

I moved to Spain to go to school for a master’s degree. I’m a pharmacist. While I was there, I discovered that I could apply for citizenship through my Sephardic Jewish lineage. I had heard something about it in Honduras, but it was portrayed as a very complicated thing to achieve. When you read the law, you understand that they are making it impossible to apply and check all the boxes. I thought, I don't have the things that they require. I don't have a Hekatia document that says my family speaks Hekatia, or Ladino for that matter.

Once I got to Madrid and started talking to people in the Jewish community, they said, “we know someone who did it.” Someone gave me the name of a lawyer who had done it for her. I met with this lawyer and I said, “Listen, I don't know if this is possible, but I'm here, willing to try.”

When my lawyer told me about [Judge Celemín’s] record, I panicked and started re-studying all kinds of crap related to Spain, history of the kingdom, the royal family, political subjects, cultural information and some other random shit. It was horrible. When it was my turn to swear, I entered this very impersonal room, and he was sitting up there, far away from the first row. He didn’t even look at me or lift his head or voice while asking the questions that I had to respond to in order to swear. When I said I couldn’t hear anything, he refrained from answering and the assistant who was also there just nodded something at me, like telling me to say “yes.” To this day, I don’t know what I said yes to.

The lawyer who met me when I was doing the first submission of papers, he was all high and mighty, saying, “You know, what I don't like about this law is that you come here,” — “you” meaning me as an Honduran — “you come here and you take things from us and you don't bring anything to the table. I'm approving you to be Spanish, but you are giving nothing to me, you as a Honduran, I don't have any benefits in Honduras from your side.” He implied this should be a bilateral thing. I remember thinking, oh my God, the whole purpose of this law is just to amend, to right your wrongs.

Luis Fernández, 36, Caracas

Luis Fernández is still waiting to see if he will become a Spanish citizen. Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro entered office in 2013, the same year the law of return for Sephardim was making its way through the Spanish Parliament. It was also the beginning of Venezuela’s migration crisis. After hearing about this law, many Venezuelans, including Fernández and his family, began to search their family trees for Sephardic roots.

More than 7 million Venezuelans have left their country in the past decade. Nearly half a million, 438,400, have sought asylum in Spain, the main destination for Venezuelan immigrants outside of the Americas.

Fernández serves as editor for the Venezuelan newspaper El Clarín, meaning “the bugle.” In July 2021, El Clarín’s editorial board ran an article with the headline “Nueva Inquisición persigue a sefardíes” (“A New Inquisition persecutes Sephardim”). The article attributed the wave of application rejections, especially among Latin American applicants, to the change in the law’s criteria requiring applicants receive a Certificate of Sephardic Origin from the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain.

Luis in Málaga preparing to meet with a Spanish notary to sign documents for his citizenship application.

My parents are from Ciudad Bolívar. My father is a journalist and I come from a family of journalists. This side of the family has Sephardic ancestry. Before the law, our ancestry was unknown to us. We came from the Canary Islands to Caracas. During the independence movement in Venezuela, there was internal migration and my family moved towards the east of the country. There they set down roots. They were all descended from Sephardic Jews who were expelled in the 1400s.

A Spanish passport is very important because it gives you access to a first-world citizenship, with all that implies for us in a country with a humanitarian crisis, or in a failed state, where the minimum wage is 6 dollars, where there is no access to healthcare or education.

In Venezuela, the people who have obtained nationality through this pathway are generally middle-class professionals with incomes that can incur all these costs. The most vulnerable population has not been able to access this because, first, they cannot pay the fees for a genealogist. They don’t have the money to travel to Spain to sign before a notary. Basically, all the Venezuelans that have applied this way have had some purchasing power.

El Clarín is a newspaper that has served Venezuela for more than 40 years. As I imagine you know, in Venezuela, we have had some problems with the press. In addition to my family having Sephardic ancestry, in Venezuela this has been a topic of great interest precisely because the country is in a humanitarian crisis. Venezuelans have seen the opportunity to obtain Spanish nationality through this pathway.

They simply don’t see or don’t respect the damage that has been done to these people who want to get Spanish nationality through this law.

The Israelite Association of Venezuela has ensured that everyone who is applying for Spanish citizenship through this law has completed all the requirements and done all the research. All of this work has been rejected by the Federation, although the Israelite Association of Venezuela is much older than the Federation, and an association that knows the history of the people that are applying. Now, the Federation has denied the certificates from the Venezuelan Association and applicants must go to the Federation to try to obtain a certificate from them.

For example, my great-great-great grandfather, born in 1750, has a birth certificate, a baptismal certificate, or a marriage certificate. And if in that paper from the 18th century, his two surnames do not appear—the two surnames of his father and the two surnames of his mother—the document is rejected. My great-great-great grandfather lived in a city of a thousand inhabitants called Segurito in the state of Táchira. He had a very strange name and his dad had a very strange name too. It is evident that a very small town is dealing with the same person, but the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain says no, they are not sure that it is the same person, and that is why the document has to have both last names.

I am not surprised by the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain because they simply don’t see or don’t respect the damage that has been done to these people who want to get Spanish nationality through this law. It seems as if they have a political motive more than a real motive to help Sephardic descendants. Beyond that, it seems that they are not valuing people with Sephardic ancestry, as if we aren’t Sephardic, or as if they see that people with Sephardic ancestry don’t have the same right to citizenship as people with Sephardic ancestry who practice Judaism.

The law was very emphatic — it was for religious Jews and non-religious Jews. From the beginning, the law’s spirit was to repair the damage that had been done in the 15th century and give nationality even to people who were not practicing Jews.

✺ Published in “Issue 5: Debt” of The Dial

PHOTO: Copy of the Alhambra Decree / Spanish edict of expulsion, 1492. Public domain.