Those Who Have Done Nothing

El Salvador’s “regime of deception.”

NOVEMBER 14, 2023

Leoncio Alfaro Rivera, 68, father of José Samuel and Hernán Alfaro, imprisoned during the regime of exception in El Salvador. Despite his wait for a knee operation, he walks every day to work his maize field.

WORDS BY JOHN GILBER & PHOTOS BY MIGUEL TOVAR

Thousands of women eke out precarious existences in camps on the Calle A Mariona: pieces of cardboard, plastic bags, a blanket here and there, occasionally a child’s plastic stool. Everything is spread out on the sidewalk in front of the walls of La Esperanza (“Hope”), the cynical name for the prison known throughout the country as Mariona. Built in 1972, in the canton of San Luis Mariona, it is the most crowded prison in El Salvador. The women sleep leaning against the walls and gates of closed businesses, or lying down on cardboard boxes, plastic bags or backpacks. During the day they stand, walk in circles, sit down, and get up again, always looking at the prison walls.

I see a solitary woman sitting on the sidewalk on an old, dirty mattress. She tells me a story: her 23-year-old son was arrested a little over a month ago. He sold fried potatoes at Arcos del Espino beach on weekends. One day, at the start of the state of exception, the police showed up and took him away, potatoes and all, at eleven in the morning. “They told me they grabbed him for illicit association, but that’s not true. He doesn’t have tattoos, he was wearing shorts and a t-shirt,” she says. Illicit association is the Bukele government’s catch all crime that roughly translates as “having something to do with a gang” and can include things such as wearing clothes, colors, or numbers associated with a gang. A few yards away, a group of women waves me over to ask what I’m doing here. When I say I’m a journalist, they start to tell me, speaking all at the same time, about their arrested children.

The walls of La Esperanza (“Hope”), the cynical name officially given to the Preventive Centre for the Fulfilment of Sentences, built in 1972, in the canton of San Luis Mariona.

“That day, Sunday, 24 April [2022] at four in the morning, they knocked on my door and only asked one thing: ‘Who do you live with?’ I lived with my son, all our papers were in order. My son came out from the bedroom. They cuffed him and brought him here. They don’t give us any explanation. All they come out to tell us are lies. First they told us we had to wait six months, and then they, the detectives, came out to tell us that now none of the arrested will be let out,” says María Magdalena Sandoval de Arévalo, and her voice breaks. I listen to her, then another woman, then another. A line forms; the group around us keeps growing. All tell stories of young men arrested in their workplaces, or during their commute, or taken from their houses very early in the morning. All had jobs and none had tattoos, they insist. To have a tattoo in El Salvador now means jail time: many gang members tattoo the numbers or letters of their gangs so any mark on the skin is seen by prosecutors as proof of criminal activity.

Verónica Escobar has two sons in jail, Elmer and Douglas. Both work with mototaxis, one as a driver, the other as a mechanic. They come from the department of La Unión on the far eastern edge of the country. I ask her about tattoos. She says to me: “They don’t have any of that. That’s why I keep showing my face here, for my sons, because I know what I have. Do you think that if they were gang members, I’d keep showing my face? No.”

Ana Molina Rodríguez comes from San Lorenzo, near the border with Guatemala, where she and her husband are farmers. At five in the morning, they went with their son to milk their cows, when the police stopped them. “They arrested him without telling us a thing,” she says. “We came and told them we brought his documents. They didn’t allow it. When I went to the local station, what was it they told me? That I should shut my mouth, because a parent is the last one to get wind of what their sons are doing.”

I listen to many women and two men, all family members of the young men who were arrested, until the group around me dissolves. The audio of the recording is one hour and 52 minutes long. Four days later, the federal forces will show up at dawn with tear gas and clubs, to evict everybody there. They will destroy the camp.

Between March 25 and 27, 2022, 87 people were murdered in El Salvador. The killers appeared to choose their victims at random: someone out to buy pastries, a man giving surfing lessons, a woman selling fruit at a local market. In the middle of this slow-motion massacre, on March 26, President Nayib Bukele — the millennial, Bitcoin-praising, self-described “world’s coolest dictator” — declared a “state of exception” to wage war on El Salvador’s long-feared gangs.

In the following days, the Mara Salvatrucha 13 gang would claim responsibility for the 87 murders: they wanted to punish the government for breaking their earlier informal agreement and arresting one of its leaders. Since the earliest years of gang violence in El Salvador, every president has made a show of being “tough on crime” while secretly negotiating agreements with gang leaders to lower homicide rates in exchange for gang member benefits in jail. Bukele was no different. What he did do differently, was decide to fill the nations prisons, and then build new prisons and fill them too, with gang members or anyone who could be reasonably believed to be a gang member, which in El Salvador, like most other countries, means the poor.

✺

I arrive in El Salvador in late April 2022, just over a month after the announcement of the state of exception, which suspends constitutional rights like those of assembly, free transit, and the inviolability of the home. Nayib Bukele and the Civil National Police are celebrating the figures of mass arrests: 3,000 people in three days, 5,000 in a week and over 25,000 in a month. On their Twitter accounts, the police publish photographs of tattooed men being pulled from underground hiding places or handcuffed and on their knees. There are patrols and roadblocks everywhere. By day few young people can be seen moving about, and when night falls, there’s nobody out.

There’s been a good deal of reporting in San Salvador, the nation’s capital, but little from beyond. I want to see what is happening in the countryside, in the rural communities the gangs never succeeded in dominating, the communities born out of the long civil war and mostly left to themselves since then. And so, on May 2, 2022, I arrive in the small, rural district of Guarjila, in the department of Chalatenango.

Guarjila was one of many communities that suffered from the “scorched earth” policy during the Salvadorian civil war between 1980-1992, which left 75,000 people murdered, 15,000 disappeared and over a million in exile. After the Peace Accords in 1992, small plots were delivered to ex-combatants and refugees. For many years, Guarjila kept its fame of being a united, organized community, but everything started to change with the open wounds left by the civil war, the appeal of guaro (sugar cane liquor), the drugs, the emigration and the dependency on remittances.

Guarjila has an official population of 2,200 inhabitants, the majority of them farmers who were or are members of the FMLN, the guerrilla force transformed into a leftist political party. This is one of only two districts in the Chalatenango municipality where Nayib Bukele did not win the 2019 elections. In fact, he lost brutally here: 1,191 votes for the FMLN, versus 171 for Bukele and 33 for the Alianza Republicana Nacionalista party.

An inhabitant of Guarjila, El Salvador, poses for a picture on her bicycle during the regime of exception. Now the streets are often empty.

From early on in the state of exception, Bukele made the logic of his plans clear: “Everyone arrested will undergo the same regime for thirty years,” he wrote on social networks. The regime consists of two meals a day, sleeping on the ground without sheets or mats, without supplies for personal hygiene. Under this new policy, the only evidence against an arrested person is their own arrest. Even so, the initiative has been widely supported in El Salvador, particularly by people living in regions formerly controlled by gangs. Although it is now common knowledge that Salvadorean gangs originated in Los Angeles, California, during the Salvadoran civil war, many hold these gangs as responsible for transforming a country of 6.5 million inhabitants into one of the most murderous places in the world. For that reason, they applaud the figures of mass arrests and the images that show half naked men tattooed with symbols of the feared MS-13 and Barrio 18, now subdued and submitted.

The state of exception in Guarjila began with the arrest of eight young men ranging in age from 16 to 35 years old that spring; the day I arrived to cover the situation, another was taken away. The Twitter account @chalateplus, a media site based in nearby Chalatenango, publishes photos of the arrested men guarded by soldiers, with texts like the one on 21 April, which declares four young men to be “members of the MS-13 that terrified the inhabitants of the canton Guarjila de Chalatenango.”

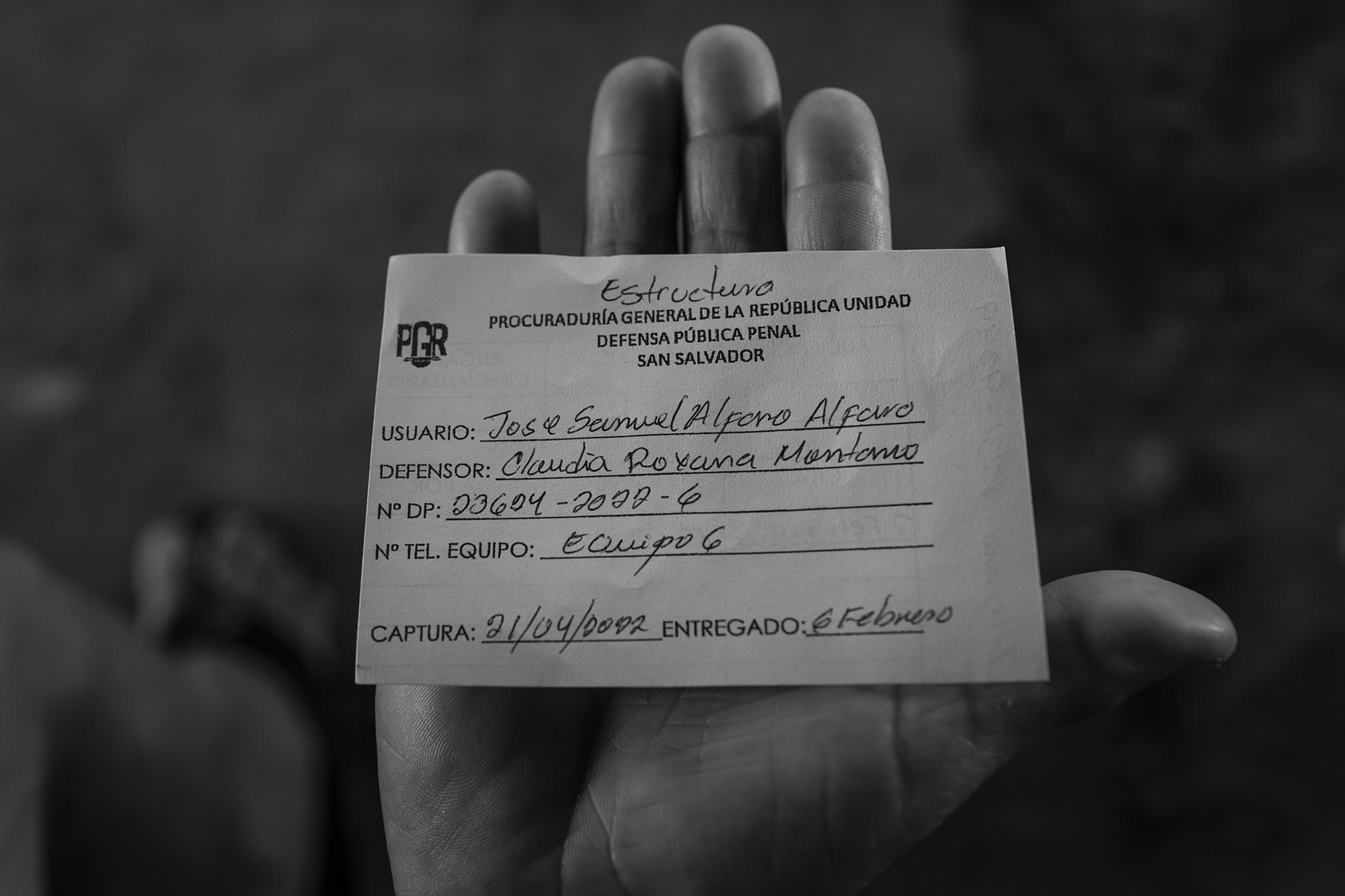

The four arrested men who appear in the image with hands cuffed behind their backs are, from left to right, Kevin Otoniel López, 29 years old; Jonathan Alexander Dubón, 19; José Samuel Alfaro, 33, and Jesús Alexander Miranda, 18. Kevin Otoniel, the tallest, looks down, his gaze is alert, as if he’d received a blow or threat. Jonathan Alexander lowers his head and closes his eyes. José Samuel and Jesús Alexander look straight ahead, resigned. None of them defies the camera. They wear t-shirts, shorts, sandals, trousers, running shoes. No tattoo or gang symbol can be seen on them; they’re flanked by masked soldiers with assault rifles.

The photograph @chalateplus published of the four young men arrested in Guarjila, which circulated on social networks in those days. “When I was there, there was no means of communication or anything, just police,” remembers Kevin Otoniel López.

I decide to go to the houses of the four men, to speak with their families and some of their employers, friends, acquaintances. They knew about each other, just like in every small town, but didn’t make up a group of friends, and none was very close to another. It might be the case that occasionally one smokes “the kind of cigarette that makes you laugh” or “goes out drinking with his friends,” if that. What unites them is their arrest on 21 April 2022.

✺

Stela Cruz moves as if she were walking underwater, with a pain on her face that resists every effort to conceal it. She’s the mother of Kevin Otoniel López. On April 21, Stela was working at the clinic in Guarjila, in charge of medical data, when Kevin called to tell her police were at the door of their home, threatening to take him away. Stela came back running just in time to see him being put in a police car. Since then, she hasn’t been able to visit him. The authorities promise her hearings, without specifying dates. “They’re doing the hearings virtually, arresting 150 or 200 at a time. You don’t have the right to a lawyer or anything,” she says. The day of his arrest “he was cooking, they didn’t even give him time to eat his lunch,” she says.

“Those boys don’t scare anyone,” says Fanny Orellana, a twenty-five-year-old woman, codirector of the fellowships program of El Tamarindo Foundation, a community space created in 1992 by John Giuliano, a New York Jesuit who abandoned his habits to work with refugees in Tijuana and later moved to El Salvador. Giuliano says that he came here to “accompany the people in the revolutionary process,” referring to both the 12-year civil war and the arduous transition to peace. After the Peace Accords, Giuliano set out to support the community’s children who had just survived the war. Over the years he got hold of enough donations and funding to create a community center promoting integral development, with one field for hockey, another for soccer, free English classes, fellowships, loans for local microentrepreneurs, support for women’s groups and classes on gender equality. In Guarjila, everyone knows this space as “El Tamarindo,” for the tamarind trees that survived the Army bombings during in the civil war; now it’s where children spend their time playing and studying.

Kevin Otoniel speaks English and worked as an interpreter for student groups from the United States who came to visit El Tamarindo. “He’s incredibly pleasant,” says Giuliano, “very intelligent and respectful. He’s no damn terrorist.” The boy sang and played the kazoo with the local ska-punk group Guarjila Alternativa Libertaria. He’d begun to study for a degree in English at the University of El Salvador, but quit during the pandemic. After that, he worked as a day laborer and helped out his mother at home; he liked to go for walks in the hills and take photographs with a drone.

I ask his mother if she knows where Kevin Otoniel is locked up. “When I asked the lawyer at the attorney general’s office, they told me Izalco prison is full, and all the most recent cases were sent to Mariona,” she says in a broken voice. “It’s like this all the time with them, the same anguish. They aren’t resolving a thing.”

✺

Teresa’s house has a corridor under a sheet metal roof, which doubles as a patio. This is where police arrested her son Jonathan Alexander Dubón, the same day they took away Kevin Otoniel López. In this case, too, the police called out from the gate, and said they’d seen someone running by. Jonathan Alexander was sitting in boxers in the shade, he’d just got back from work and was about to eat something. He put on some shorts and a t-shirt and went to the gate. They cuffed him immediately, without further explanation. “They took him to the park. Then they took photos of him and went away with him. We haven’t heard anything else. I went to the attorney general’s office to bring them documents about the project where he works, and they told me they’d already got them in Mariona,” says Teresa, shaking her head at the absurdity of the situation.

Jonathan Alexander is 19 years old. Until that day he was working at Mi Granja Guarjila (My Guarjila Farm), a microbusiness that grows vegetables and breeds pigs. The business was doing well. They took pre-orders and always sold out. “In 2019, Johnny had plans to migrate,” says Marcos Antonio Rivera, president of the company, but after talking with the team of Mi Granja he decided to stay. “I can attest to how he’s moved up in the world in the three and a half years of this project. You can see when a young man wants to improve himself.” Jonathan Alexander decided to take the next step. He applied for a two-year work visa as a butcher’s apprentice in Canada, where he could study and work at the same time, with the trip paid for. The Canadian embassy called the house the day after his arrest to inform him they’d granted his visa.

✺

José Samuel Alfaro is the third young man, from left to right, who appears in the photo by @chalateplus. “I can’t bear my depression anymore. I don’t know where my son is. I haven’t been able to see him. I don’t have money to go look for him and take him money. They grabbed him from the workshop, where he was working under a car, without giving any explanations to the owner. It doesn’t matter where you are, that’s just not right,” says Julia Alfaro, his mother, speaking with a mixture of exhaustion, anger and desperation, sitting in a gently swaying hammock, looking at the ground as she swallows her anguish.

Julia Alfaro, mother of a young man unjustly arrested and jailed by the regime of exception.

Marlo Morales, owner of the automobile workshop Los Primos where José Samuel worked from six in the morning until six in the afternoon, says the arrest was carried out with arrogance: “They said that we’re in a state of exception, and they have the authority to enter wherever they want.” The police asked who had a criminal record, and José Samuel admitted he’d been arrested for bearing and possessing arms in 2013, but had already completed his sentence. “We’re going to take him away, you can come look for him in prison,” the police said.

José Samuel was born in a refugee camp in Honduras, after his parents were forced out of the country. He arrived in Guarjila as a boy, during the FMLN’s drive to help refugees return during the last years of the war. He’s held many jobs: migrant farmer in the United States, welder, circus worker responsible for assembling and taking apart the show, and goalkeeper for the Tamarindo hockey team, which won a Central American championship. He had been apprentice mechanic and night guard at the workshop Los Primos for two years.

Julia brought a letter to the authorities signed by lawyers confirming her son had fulfilled his previous sentence, along with another from his employer, but they didn’t want to receive them. She begs for a human rights commission to come to El Salvador to investigate Nayib Bukele and his regime. “There are no human rights. None. He’s taken away all rights,” she says, and lowers her eyes. “Señor Bukele asked the young people to vote for him, and look at the consequences, he has all the young people here in the community terrified, now they can’t even go out to buy anything.”

John Giuliano takes out a photograph and shows it to Julia Alfaro. “Look, there’s José Samuel,” he says, pointing to the team’s goalkeeper. “Is that my son?” she says, and starts to cry. Giuliano hugs her. “I don’t even have a photo of my boy,” she says.

Back to the photo. Jesús Alexander Miranda, eighteen years old, looks at the camera. He loves motorcycles. His mother was able to buy him one with the money sent by his father, who works as a migrant carpenter in the United States. As soon as he had a motorbike, Jesús Alexander took it apart. Completely. His mother almost had a heart attack. For three months, he tried to put it back together, piece by piece, watching tutorials on YouTube until he could get it started again. That’s how he learned mechanics, and at the age of sixteen he installed a repair workshop in the patio of his grandmother’s house. That’s where the police arrived that fateful 21 of April, at two thirty in the afternoon. They asked for his ID and he gave it to them. One of the policemen said: “Now we just need one more, let’s finish this trip.” They led him outside to the street, and when his mother, Deisy Miranda de Serrano, asked where they were taking him, they answered her: “He’s going to make a statement, he’ll come back soon, señora.”

Deisy, who like many people with family members in the United States has a few more resources, got into her car and followed the police. She waited outside the station that day and the next, without receiving information. At three in the afternoon the next day, she saw the arrested men being boarded onto a bus. Someone told her they were being taken to Mariona. No more information was given to her, but at six that night the photo was published in @chalateplus. “Those horrible things they said about how [the young men] terrified the community. They aren’t true. It isn’t true what they say, that ‘those who have done nothing, have nothing to fear.’ Now this is a ‘regime of deception,’ because whole families are left in tears,” says Deisy, citing rhyming the Spanish translation of Proverbs 28:1, los que nada deben nada temen.

A Saturday of 2023, despite the regime of exception, Jesús Alexander Miranda and four friends watch the sunset over Guarjila, after going up the hill in motocross.

Among other recent captures: Marvin Dubón Guardado, a 16-year-old boy arrested two days earlier, at seven in the morning, when he was going to buy bread for his grandmother.

✺

In Guarjila they say there are no gangs, though there is violence, just like anywhere. But Alfredo Hernández, mayor of Chalatenango, tells me that parents are the last ones to know what their children are doing. He admits the municipality is “one with some of the lowest rates of violence,” but even so, from his office decorated with photos of Nayib Bukele, he defends the state of exception. The interview lasts for half an hour, during which the mayor plays with his ballpoint and looks constantly at a female adviser who doesn’t lift her eyes from her mobile phone. He says everything is constitutional. There might be errors because “no process directed by humans is perfect,” but it doesn’t matter if it’s a difficult period and some have to “sacrifice” a few months of their lives behind bars, if “the country is cleaned up.” If the system works, “they’ll need to convict and sentence more than 90% [of those arrested],” but even so, “we hope people who aren’t involved at all can prove their innocence, right?”

“The mobs are disappearing in El Salvador. The mafia of the State has taken their place,” says Juan José Martínez, about the regime of exception.

I look for other official sources. María Chichilco, the legendary commander of the FMLN who engaged in combat from mountains and ravines, is today a member of Bukele’s cabinet, serving as Minister of Local Development. “I’m going to tell you the truth with all the pain in my heart: I believe this big sweep they’re making is good, because I know terrible facts,” she says in the patio of her house, in a pleasant, even affectionate tone of voice. She speaks of executions of poor people by gang members, of unstoppable violence, and she weighs the number of innocents being arrested. “There must be some. A few will get caught in the nets meant for the big fish. But I’m going to tell you something, the vast majority there are at least a little compromised. They’re involved in some trouble, or have some connection. Those who’ve done nothing will be released, but the immense majority inside are guilty of something.”

Her confidence in the process doesn’t convince me, and I look to speak with someone from the police. A detective refuses, but later another official consents, asking that his name not be revealed. He claims he didn’t want to be a policeman. He was a guerrilla fighter and his commander ordered him to enlist in the new National Civil Police, after the signing of the Peace Accords. He knows the operations all over Chalatenango well, and says he doesn’t know about any gangs in Guarjila. When asked why the young men were arrested here, if there’s a quota to fill, he answers bluntly: “We have to grab around 50,000, I think. Yes, there is a small quota: 25 daily, or 30, something like that. We have to meet a certain quantity every day in each department. Yes, there is a quota.”

✺

Midway through May 2022, a few weeks after the arrests, the streets of Guarjila are almost empty. Boys and girls walk to and from school without stopping to play in the parks or sports fields. I walk through community and go back to visit the houses of the arrested young people again, to ask if there’s been any news. Their family members always receive me with faces twisted by pain, and the answer is the same: nothing.

Julia Alfaro has come back from the attorney general’s office in San Salvador, where they told her they don’t know anything about her son. She’s afraid they’ll disappear him. As she’s saying this, a young man I didn’t see before comes out of his bedroom and sits in the patio with us. His name is Hernán, he’s thirty years old, and he’s José Samuel’s younger brother. He works as a builder’s assistant and is the father of two girls. Hernán tells me about how much José Samuel likes hockey and also how much he likes to style his hair, something at the attorney general’s office they said was proof of “illicit association.” For Hernán, the state of exception has a clear modus operandi: “The ones who are going to pay are us here, the ones in these rural districts, the poor,” he says. He adds that the regime scares him, that he doesn’t leave his house out of fear he’ll be arrested, that he only goes to work; that he fears the police more than gang members. And for good reason: two months later, in July, the police will come for Hernán. They’ll take him from his house at four in the morning, when he was already awake and about to eat breakfast, before heading to work. He’ll be taken to prison in San Salvador, held without access to a lawyer or family visits, and “taken” before a judge in a video call with several hundred other recently arrested inmates.

Two days after this meeting, on my final day in Guarjila, I go visit the home of Stela Cruz, Kevin Otoniel’s mother. She tells me that at the attorney general’s office they told her not to worry, that in four or five months there will be another virtual mass hearing, where all the same they might sentence him, leave him for another six months in prison while they keep investigating or let him go. “I don’t watch the news anymore because it makes me feel so sick. They’re dying in the prisons, they’re taking corpses out of there every night.”

One of the sports fields at El Tamarindo, “a place of learning” says Noemí Alfaro Ayala, one of the inhabitants of Guarjila, “a place of recreation, where one can play and enjoy oneself a while.”

I monitor the situation in El Salvador over the next few months. On July 14, 2022, the Salvadoran police and soldiers carry out a raid in Guarjila at dawn and arrest ten people, among them Hernán Alfaro, José Samuel’s brother. John Giuliano, the founder of El Tamarindo, phones me, worried; two weeks later, he organizes a public event to hear the concerns of the community — against the prohibitions of the state of exception — with the bishop of Chalatenango, Oswaldo Escobar Aguilar. The bishop was the only public figure who criticized Nayib Bukele during in an interview with me. He told me the state of exception is aimed at the marginalized working class, and that “if at all, it should last a week. If at all.” In contrast, the state of exception lasted for all of 2022, and remains in force. Every month the legislative powers extend the regime another thirty days, an anticonstitutional maneuver the judges chosen by Bukele permit.

✺

I return to El Salvador. It is March 2023 and Guarjila has spent eleven months living in fear. Twenty-eight people have been arrested, and out of all of them, only eight young people have recuperated their freedom, though not in its totality: seven still have charges against them, and must present themselves to sign a document every fifteen days before the authorities in Chalatenango or San Salvador. Three of the liberated were in the photo in @chalateplus; only José Samuel remains in prison. I look for the freed men, I want to listen to them. Some ask me to quote their names; others request anonymity. But all want to talk about what they’ve lived through.

I write down the details of the recently freed in my notebook. Marvin Dubón Guardado was arrested at seven in the morning on his way to the store. José Samuel Alfaro and Jesús Alexander Miranda, at two in the afternoon in their workplaces. The others were arrested at their houses: Kevin Otoniel López and Jonathan Alexander Dubón, at two in the afternoon; another young man, Adán Alfaro Cruz, at four, two more — who prefer not to be named — between two and three on the morning of 14 July.

All are accused of being gang members. The police took photos of them. Many of the photos were taken “just because they felt like it,” someone says. Kevin Otoniel didn’t want to pose until they threatened and forced him. They tried to make Jesús Alexander sign a document with a false testimony: “The police told us to sign three pages… I told them I wasn’t going to sign anything without reading it. I read it and no, man, it said various things that… didn’t happen. That they’d grabbed me in the park with three other people, gang members, something like that, that we were… I don’t remember… we were terrorists, it said. That’s just not true. They came to take me from my grandmother’s house.” They say first they were taken to different prisons nearby. Marvin was taken to a center for the imprisonment of minors and the rest were taken to Mariona.

Hortensia, his grandmother, had told him: “You shouldn’t go out”, but Marvin answered: “If you haven’t done anything, you have nothing to fear.” Hortensia shows a photo of her grandson handcuffed to a tree.

Jesús Alexander remembers: “Once we got there, they took us out from the bus, all hunched over. Then they made us go inside on our knees, moving fast over something like gravel, it was all hard and jagged and really painful. All of us had busted up knees, there was a lot of blood, you could even see the bones of some. And [when] we arrived, it was to go at us like piñatas, beating us. They took us to shave off our hair. And when they led us out again, they beat everyone with clubs. They beat me on the back, and finally, they gave me a kick here [he points to his ribs]. And fuck, it was a long time before I could drink anything after that. I couldn’t even go to the toilet after that blow.”

The arrival in Mariona was brutal. They were received with shouts, and never with fewer insults than “Sons of a motherfucking bitch!” They moved forward, handcuffed in pairs. The young men in the photo were taken to the third level. And in the cells, the worst began. “Every time you went down the stairs, they beat you with a club… Here, right here, they hit me in the ribs and for like fifteen days I couldn’t sleep on that side. Only the other side. And here [he points to his back] I was bruised all over, like they did it with a marker. Wherever you went, it was the same: beatings and more beatings with clubs,” one of the young men says.

“We got there, and for the whole day, there was no food, no water,” says Jesús Alexander. “We spent a month and a half without water to bathe ourselves, and only sips of water all day. And the food, the first time they gave us some macaroni, it was nasty. The food was already rancid. Later they moved us to another sector. It was worse there because that’s where it was dirtiest. A lot of welts appeared on my body. In fact, I still have some little sores filled with pus on my skin. And fuck, they didn’t give us medical attention. Nothing, nothing. Everyone there dying, and nothing. No joke, in that sector two there wasn’t any water.” Confronted with the lack of provisions for water, food and the basics of personal hygiene, families must buy supplies and leave them in a drop box. They’re known as “packets,” and are delivered to prison guards. Jesús Alexander’s mother bought him several, but only a portion of some of them arrived.

✺

The young men say that in cells designed for 60 people, there are between 120 and 260 people living there. They’re much more cramped and uncomfortable than even in the first photographs of the Salvadoran prisons released to the media by Nayib Bukele’s government, which showed the prisoners seated, semi-naked, body next to body, without any space to stand. It is the prisoners themselves who attempt to install some kind of order: they choose one leader per cell to define who sleeps where and at what time, because there’s only enough space to do so in shifts. This leader also decides how water and food are distributed, prevents arguments, and maintains communication with the guards. All of the young men tell of the thrashings they were given, but none speaks of a single confrontation amongst the inmates. They say not even the real gang members got involved with the rest of the prisoners. And fights were impossible: whenever there was any noise, the guards showed up immediately to give beatings and spray pepper gas into the cells.

“In the cell where they took me, there were four rows of cots with three levels, nine cots in each row. Two of us slept in each one, facing different directions, and people also slept on the ground and in the corridors. There were people who slept in the bathrooms, who got more illnesses, more skin infections. They gave us tortillas with beans, and coffee mixed with something to decrease sexual energy. Every day they put that in, something with an ugly taste. In my cell there were 220 people. Once I saw how they tied someone up with his hands cuffed and hit him with clubs. It was torture. Each day between eight and ten people died, just in our sector,” says a released prisoner who requests anonymity.

“Those who had tattoos, not necessarily belonging to gangs, but artistic tattoos, got hit more. Because from that bus, where there were fifty of us, at most there was one gang member in the group,” says Jesús Alexander.

Beatings, torture, overpopulated cells, lack of water, food, medicine and medical attention. Absence of legal counsel. Illnesses, theft of the packets sent by families, psychological torture and death. Death by blows. Death by malnutrition, by dehydration. Deaths denied and hidden in the figures of zero homicides published on Twitter by Bukele himself: all of that has been the state of exception, as much for the real gang members as for the thousands of people who never formed part of MS-13 or Barrio 18-Revolucionarios or Sureños, the other big gangs in El Salvador.

Marvin, the 16 year who was buying bread for his grandmother when he was arrested, lives in terror. Weeks after his liberation, the police returned: “They came at three in the morning. They told me they were going to arrest me again. They kicked the door and entered with rifles. One gave me a kick with his military boot and shouted: ‘Get up now!’ They inspected the house. Then they made a call and I heard someone say: ‘No, not the minor.’ That same night they took away three people from the community. One died, the others are still locked up.”

Today one doesn’t flee from the mobs, one doesn’t flee from the gangs, one flees from the government, says his grandmother.

Jesus Alexander repairs motorbikes in the workshop he set up in the patio of his grandmother’s house.

I know a young man who grew up in a neighborhood controlled by the gang Barrio 18 Revolucionarios, in the north of San Salvador. I’ll call him Iván. His family first had a clothing shop, and then a pupusería (shop that sells stuffed corn tortillas), in the closed-off, labyrinthine streets of the neighborhood. They did well. The father emigrated to United States, where he economically supported the family, but never came back.

One day, fifteen years ago, gang members showed up at the pupusería to charge rent, the euphemism gangs use for extorsion: a hundred dollars a month, more than half of the minimum wage. The family paid. Iván saw the gang members around and thought he wanted to become one of them. But one day, a gang member challenged him to a fight. The two were both fifteen years old. Iván refused; he didn’t want to fight. A couple days later they kidnapped him, brought him to a small vacant lot, surrounded him and told him that for having offended the gang member who challenged him, they were all going to beat him simultaneously, for a minute. A man tried to knock him to the ground, and Iván resisted, until the man took out a big knife.

“All of them beat me for like a minute,” says Iván, as he drives through the streets of his childhood neighborhood. “I started to shout that I couldn’t take anymore. They kicked me in the ribs so I’d uncover my face, which was like the prize for them. The next day I didn’t go to school. I had shoes marks all over my body.”

Afterward, Iván started to go to church because “they respected that a lot.” Another day a member of the gang called him from prison: “He said to me: ‘We know you go to church. That’s good. But if we find out you’re only going as a bluff, so we don’t get involved with you, we’re going to kill you.’ I was afraid they were going to come and take me from my house at night. I lived with that psychosis at 15 years old.” Iván kept going to church. One day, the gang killed two of his neighbors. The next day, they telephoned his mother asking for three thousand dollars or else “the next corpse will be my brother and me. Some people helped us get a taxi and we got out of there.” The family closed the pupusería, left the house and took refuge with family members in another part of the country. Uprooted.

Now, moving through these streets he had to flee, Iván speaks of the violence he experienced in his childhood. “In San Salvador you suffered a lot. I’ve seen so many people die like this, in front of me. Somebody walks up with a pistol and pow, pow, pow! Here two of my wife’s cousins were killed. Do you see that man? His son is a prisoner, and they killed his wife in jail. That woman there, they killed her sons. That was the gang’s bakery.” Every street, every corner, retains memories of fear. With so much violence around, it doesn’t come as a shock that when I ask Iván his opinion of Nayib Bukele and the state of exception, he says: “That is a great joy. I saw my wife’s aunt cry over her two sons on the same day. Today we can enter this neighborhood without any problem. My wife and I bought a house.”

✺

I return to Mariona. It’s March 2023, a year since the state of exception was declared. Nayib Bukele has spent the last few weeks celebrating the construction of a new maximum-security prison he calls the Centre for the Confinement of Terrorism. It’s in Tecoluca, San Vicente, some 75 kilometers from the capital, and has a capacity for forty thousand prisoners. According to the government, around 2,000 inmates have already been transferred from Mariona and Izalco to the new prison. Here in Mariona, the police have now evacuated that camp, which was a living image of the general desperation, though the emotion remains. The stalls with supplies for prisoners have been pushed a little further out, toward a corner, a parking lot and opposite the big door of a church. The mothers don’t camp out in front of the walls of La Esperanza anymore, but they wander about on the sidewalks in anguish.

I haven’t been here even five minutes before a woman asks me what I’m doing. As soon as I answer, she starts to tell her story: the police took away her son Ernesto, 22 years-old, from their house. He’s a mechanic. At the attorney general’s office they tell her she must wait twelve months before they can investigate her son’s case. The mother is named Ana, and sells fruit. She makes barely eight dollars a day, and now has to come from Cojutepeque—forty kilometers away—to buy and deliver the packet on which her son’s life hangs by a thread. Her great efforts might be in vain: “The packets aren’t being given to them. Every fifteen days I come to drop off the packet. That’s 60 dollars every 15 days. He’s my only son, and since they brought him in September, I haven’t heard a thing about him. Here they don’t give any information at all,” she says.

It’s the same story and the same pain: arbitrary arrests, lack of information and the business of the disappearing packets. I talk with a neighbor in the canton San Luis Mariona, whose house lets her see inside part of the jail. She set up her packets business from the very start of the state of exception, and came to earn between 800 and 1000 dollars per day, until she was evicted with the rest of the camp. Since then, the police have come back to evict her five times. At her current post, she shows me a kind of menu with different prices, for what she calls “state of exception packet kits.” It ranges from 35 to 125 dollars. Now, she says, on a good day she makes 450 dollars, and on a bad one, around 150. Even so, she doesn’t take pleasure in the tragedy of others that nourishes her business.

“We’re ruined here in El Salvador. They’ve put away several gang members, but a lot more innocent people than gangsters. It’s an injustice: this is death in life,” she says, when I ask for her opinion. She, who spends her life stationed outside the prison, addresses the rumors about corpses being transported from the jail: “You should see how many ambulances leave from there, early in the morning,” she says. “Tuberculosis is common. You can hear the screams at night from those who are hungry, sick, dying. They take them out to the fields, and whoever raises his head is beaten back down.”

Neighborhoods that were once controlled by gangs are now calm. But all through the country, rural communities like Guarjila are also being left alone and terrified. And so, just as Iván, and surely many others like him, lived in fear that gang members would take him from his house at dawn, now thousands of young people live in fear police and soldiers will take them from their houses at dawn and put them in hell. And so, just as Iván’s aunt by marriage cried over her two sons, at the close of this report, Julia is still crying over her two sons in Mariona, who remain incommunicado. To exchange one terror for another only adds more terror.

Some prisoners who preceded the regime of exception have entered into a “process of trust”: they are given jobs and the permission to receive food and clothes.

This article, produced with support from the Ford Foundation, was originally published in Gatopardo. It has been edited and translated.