Archives of Atrocity

Discarded documents from Assad’s regime offer clues to Syrians searching for lost family and friends.

JULY 24, 2025

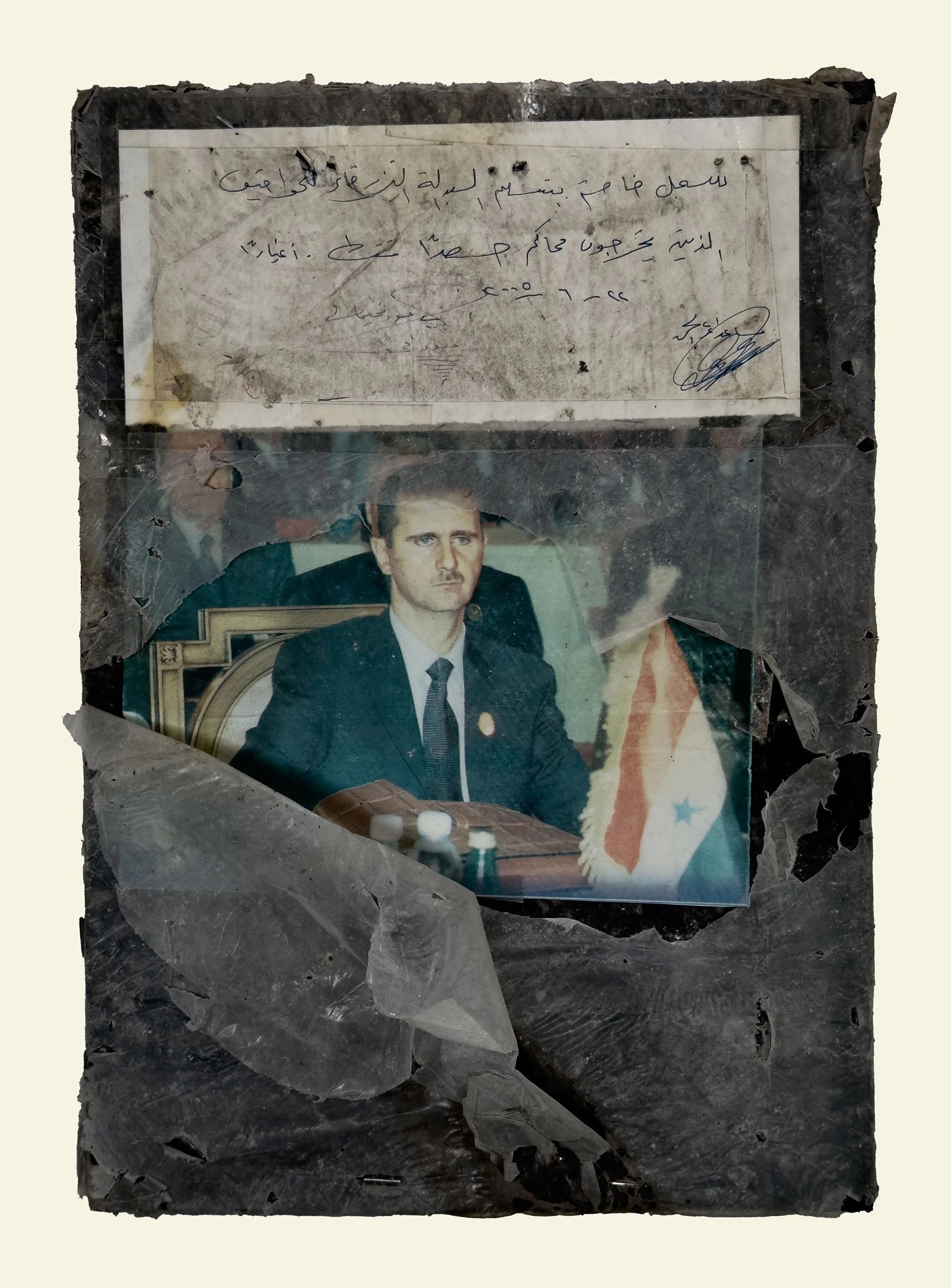

Over several trips to Syria, I’ve documented the country’s transition since Islamist rebel group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) ousted dictator Bashar al-Assad in December 2024. Up to 200,000 people were disappeared or went missing under the Assad regime, including thousands of children, according to human rights groups. After the takeover, facilities long hidden from public view — military bases, prisons, intelligence branches — were in disarray, their secrets exposed. Families rushed to the prisons, intelligence branches, air bases and government offices, desperate to find out what had become of their missing loved ones.

In the first week alone after the fall, I photographed documents and objects at the sites before they disappeared forever. Inside the buildings I visited, documents were piled high, despite attempts by the former regime to destroy them — a vast trove of evidence exposing the abuse and corruption of Assad’s regime. There were entire rooms of carefully preserved archives detailing the depth of Assad’s brutality: meticulous records of those arrested, notes on bribes paid, forced confessions, interrogations and prisoner exchanges, lists of medicines given, employee rosters, handwritten logs by doctors containing post-torture interviews, family photos of children and hundreds of IDs of those disappeared by the regime.

Sednaya prison — dubbed a “human slaughterhouse” by Amnesty International — opened for the first time in 13 years. When I entered days after the Assad regime had collapsed the air was thick with dust, and the floor was blanketed in paper: interrogation files, prisoner ledgers, employee lists, execution lists — layer upon layer of evidence of the regime’s crimes. Families searched on their knees, through papers and books, tracing names in fading ink. In the nearby women’s detention facility at Mezzeh Military Airport in Damascus, small clay heart decorations inscribed with messages were hanging alongside crayon-colored drawings of peaceful homelife — a kitchen table, a garden, a child’s bedroom. The pictures were sketches of a world the prisoners had long been cut off from.

Beneath the Air Force Intelligence Directorate Headquarters in Damascus, behind a blown-out basement wall stood crates of hard-drives and obsolete surveillance gear. Floor to ceiling archives had been incinerated, and hallways were left dark with ash. At the Mezzeh Military Airport in southwest Damascus, toppled filing cabinets and banker boxes overflowed with evidence of the disappeared.

With every day that passes, more of the evidence from these buildings is lost, trampled or scattered by the wind. Rooms that, days after Assad was ousted, were covered in six inches of documents, have been looted and now lie empty. Each document holds a clue to the fate of someone’s loved one.

The task now is to preserve, with legal integrity, evidence of the Assad regime’s crimes — to transform these thousands of photographs, documents, and found objects into prosecutable evidence. But this moment is fragile. The evidence is quickly vanishing as is the narrow window to preserve it.

Syria has moved into a new uncertain chapter. In January, Ahmed al-Sharaa, the leader of HTS, was named as interim president of Syria. The work of rebuilding trust — and delivering justice — is only just beginning. Groups like Caesar Families Association and The Syria Campaign have called for justice and for answers for Syrians whose family members have disappeared, but many people are still waiting for the government to establish a system for them to search for their loved ones and for accountability. Frustration is growing. Hope that the new leadership would act swiftly has been replaced by disappointment.

On May 17, 2025, a small but symbolic step was taken. A presidential decree announced the creation of the National Transitional Justice Commission and the National Commission for Missing Persons. These bodies are tasked with exposing the crimes of the past, helping families learn what became of their loved ones and ensuring accountability.

It’s a beginning — but only that.

An employee ID card found in Air Force Intelligence Headquarters in Damascus.

An X-ray discarded on a floor littered with diapers, house keys, an ISIS flag and IDs in Branch 215, a notorious detention facility in Damascus run by the Military Intelligence Directorate.

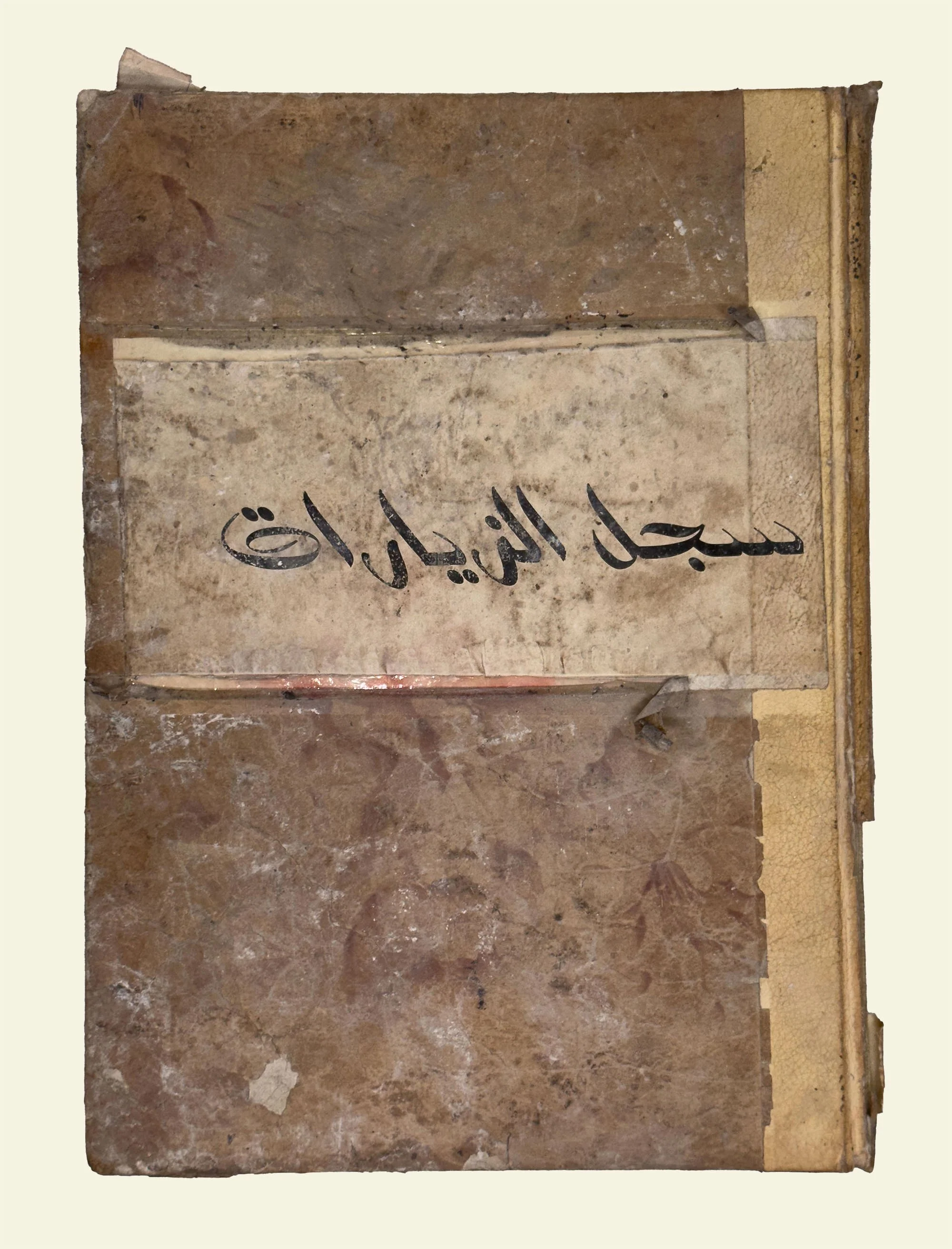

A book titled “Visitors’ Log” found in Sednaya prison in Damascus.

Book of records found in Sednaya prison in Damascus.

The photo copy of foreign property development plans for Damascus found in Branch 215 in Damascus.

2 sim cards found in an office at Mezzeh Military Airport in Damascus, surrounded by shredded papers and bullets.

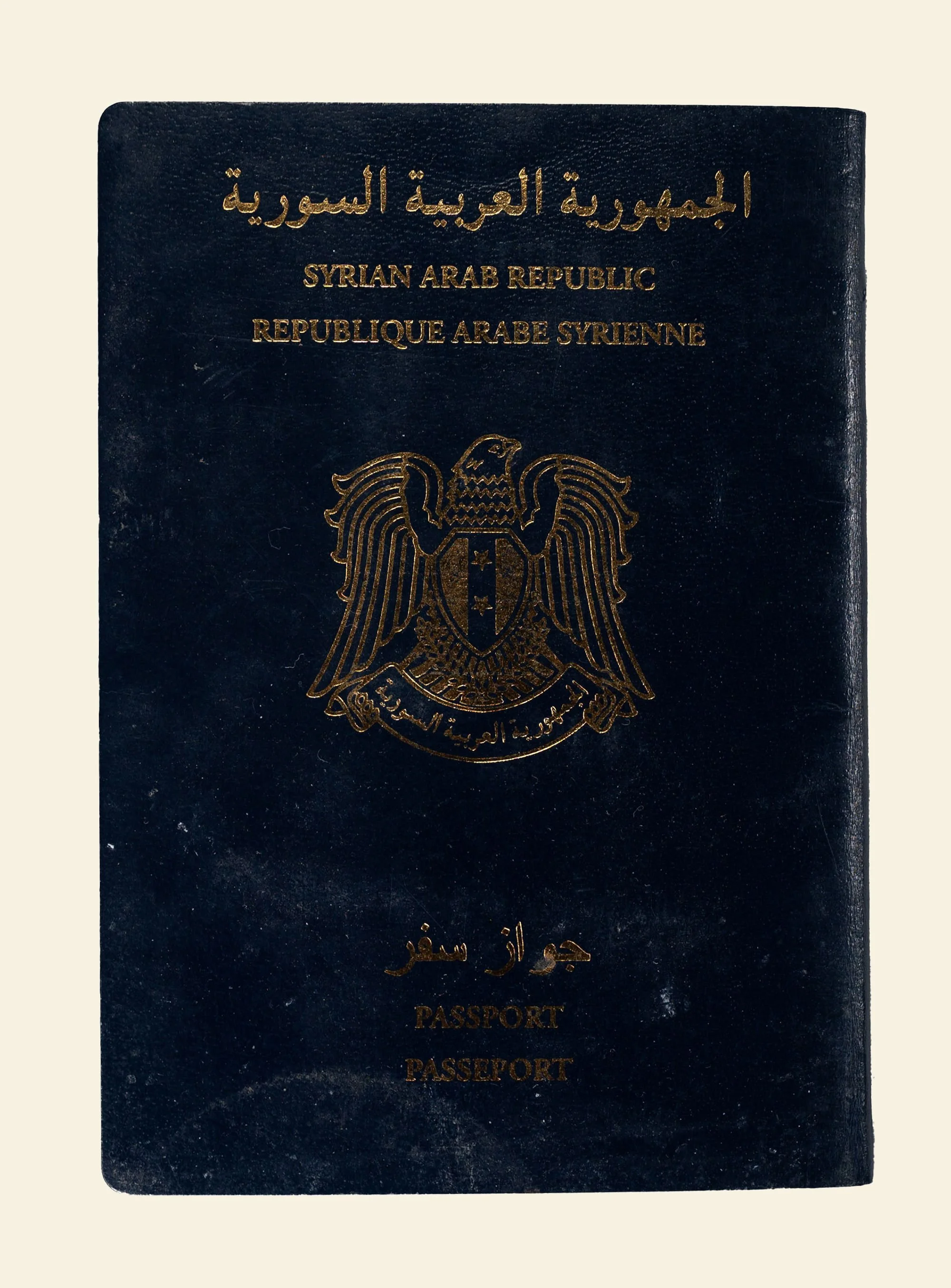

A Syrian passport found in Branch 215 in Damascus, in a box of passports from dozens of countries including Britain, India, Iraq, Tunisia, Sudan and Germany.

A photograph of a birthday cake found in a family album in Assad’s family home in Damascus.

Clay heart shaped decorations inscribed with messages found in the women’s detention facility in Mezzeh Military Airport in Damascus.

Left: “The most beloved of all — my mother”

Right: “I would give my soul for you”

An office key found in Mezzeh Military Airport office in Damascus.

USBs found in an envelope with plane tickets to Saudi Arabia, in Air Force Intelligence Headquarters in Damascus.